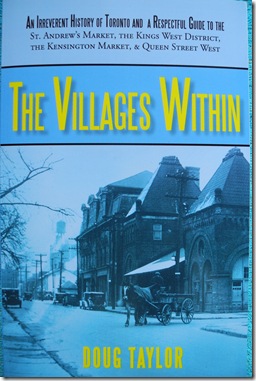

The following account of the War of 1812 is from the book, “The Villages Within,” nominated for the Toronto Heritage Awards. In a tongue-in-cheek manner, the book chronicles the history of Toronto from its founding by Governor Simcoe until the Confederation years. The book also provides detailed studies of the Kensington Market, Queen Street West, the St. Andrew’s Market, and the Kings-West District.

On June 18, 1812, war with the United States commenced. Unlike today, York’s business community did not welcome a summer invasion of Americans charging across the border. After several victories on the battlefield, General Brock was killed at the Battle of Queenston Heights. The news of his death struck the fragile community of York like a thunderbolt. Many feared the war would be lost without his leadership.

In April of 1813, the American sailed across Lake Ontario and attacked York. When it was obvious that the struggle to secure the fort was doomed, the British lit a fuse to the powder magazine and swiftly retreated. When the powder detonated, it rained shrapnel for a radius of over a mile. Very little of Fort York survived. During the years ahead, debris from the explosion was found in the fields and embedded in the trees. It is possible that the older trees of the St. Andrew’s Playground of today were among them, as photographs taken around 1910 reveal that they were already mature tree at that time.

When the American invaders entered the town, they set fire to the parliament buildings and carried away the parliamentary symbol of authority, the “mace.” In addition, while in the building, they discovered the ceremonial wig of the Speaker of the House, and mistakenly thought it was a human scalp. When the troops returned home, they claimed that the British were “scalpers.”

Today, I glow with pride when I see the descendents of these “scalpers” outside the Air Canada Centre, particularly when the Leafs play against the Habs. I have even seen them around the opera house and Roy Thomson Hall. Some unkind souls say that Torontonians will scalp their grandmothers if the price is right. We do indeed honour our traditions.

In addition, today, some state that the infamous wig from the War of 1812 eventually surfaced on the head of Mel Lastman, who wore it honourably and ignored the surreptitious smiles, claiming it was a hair weave. I am certain they are wrong.

In 1934, in honour of the city’s centennial, the mace was returned to Toronto and today is on display at Fort York. No one knows the real location of the speaker’s wig.

*

One of the best-remembered stories of the War of 1812 was the exploits of Laura Secord, who, contrary to rumours, was not Canada’s first chocolate maker. She “sallied forth” through the “enemy-infested woods” of the Niagara area. Have you ever noticed that in most heroic tales, the heroes “sally forth” in the “dead of night” and invariably choose “enemy infested environs”? Such wording is a prerequisite for these stories.

Be as it may, Laura’s deeds were impressive.

Late one evening, little Laura overheard a few American troops discussing plans to attack the British near the town of Beaver Dams on the following day. She knew that Lieutenant James Fitzgibbon was on a military stake out, so she sallied forth in the dead of night through the enemy-infested woods, employing a cow as a decoy. Thinking she was a mere farmer’s wife, the American sentries allowed her to pass through their lines. As a result, Laura was successful in warning Fitzgibbon of the impending attack.

In retelling the events of that portentous night, some misguided soul thought that Laura had confused a “stake-out” with a “steak-out,” and that was why she brought along the cow.

Due to her information, Fitzgibbon successfully captured 450 enemy infantrymen, 50 cavalrymen, 2 field guns, and a partridge in a pear tree. These figures are accurate, although the “partridge in a pear tree” is my own addition. It seemed to be a natural conclusion to the sentence. However, it’s true that he accomplished his victory by bluffing the enemy into surrendering by offering to prevent the Indians from attacking. The Americans were unaware that Fitzgibbon commanded just forty-eight soldiers and a band of only four hundred Indians. The enemy force had been superior in both numbers and artillery.

Fitzgibbon was highly praised for his quick-witted actions.

However, according to some rather dubious sources, because of his ability to bluff, in the years ahead nobody would play poker with him. Some say that to compensate for this sleight, they bestowed on him the official title of “York’s First Bluffer” and named the Scarborough Bluffs after him.

This is all historic bumf.

*

Following the war with the United States, on September 29, 1815, Lieutenant-Governor Gore returned to York and resumed his role as governor. He was a wise governor, wise enough not to hang around the colony during a dangerous war.

Book is available on Amazon.com. It may also be ordered in any Chapters/Indigo store or ordered from their web site.

Save time and order directly from the publisher, follow the link : http://bookstore.iuniverse.com/Products/SKU-000175211/The-Villages-Within.aspx

For further information on the author, visit his Home Page :https://tayloronhistory.com/