The CNE Grandstand in 1956, taken with Kodachrome film with my 35mm Kodak Pony camera from the top of the Ferris Wheel on the midway.

Toronto’s CNE Stadium creates different memories for different people, depending on whether a person remembers it as a baseball stadium, or as a grandstand where Canada’s most spectacular stage shows were held. When the CNE Grandstand performances ended in 1968, it was an indications that the annual fair was no longer the most important late-summer event in Toronto. The CNE continues to attract over a million visitors annually, more than any other fair in Canada, including the Calgary Stampede. However, its prominence in the life of the city has greatly diminished. Canada’s Wonderland, Rogers Stadium and the Ripley Aquarium are a few of the entertainment venues that now compete with the CNE.

Today, it is difficult to conceive of a world without the internet—Facebook, Twitter and blogging. When I was a boy, smart phones were confined to science fiction where the comic-book hero Dick Tracy sported a 2-way wrist-radio that allowed him to transmit messages. Now, the technology is a reality. However, the CNE commenced long before the era of the internet, at a time when agricultural and industrial fairs were important to disseminate information about the latest horticultural trends and technological advancements.

During the 19th century, fairs were held at various locations throughout the province, Toronto hosting them several times. In April 1878, on land on the north side of King Street West, near Shaw Street, a highly successful one was held, attracting over 100,000 people. It inspired Toronto’s City Council to seek a site for a permanent fair, to be held annually. In 1878, the city leased the western portion of the Garrison Reserve, to the southwest of Fort York. On March 11, 1879, the Provincial Legislature passed “An Act to Incorporate the Industrial Exhibition Association of Toronto,” to allow the city to incorporate a fair.

The first “Industrial Exhibition” opened on September 3, 1879, for one week, the price of admission 25 cents. There were 23 buildings, one of them a grandstand containing 5000 seats. During the next few years, it hosted various events, including horse races, sports, fireworks, livestock judging, and stage shows. The fair was so successful that in 1892, the grandstand was rebuilt and expanded, doubling its capacity to 10,000 seats. The same year, the fair grounds became the first in the world to be electrified, making it possible for the grandstand stage shows to be larger and more extravagant. Another advantage was that they could be held after sunset.

In 1906, the grandstand burnt to the ground.

Ruins of the grandstand in November 1906, following the disastrous fire. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item, 0012.

The Grandstand that replaced the one that was destroyed by fire in 1906. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231, Item 1253.

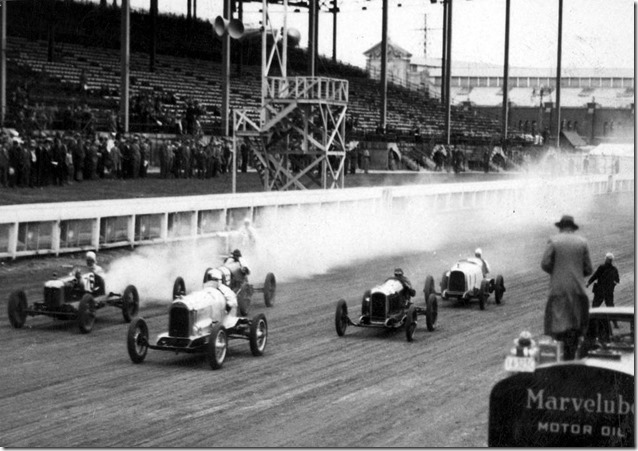

Auto race in the grandstand in 1926, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 1399.

The architect G. W. Guinlock designed a new stadium for the Industrial Exhibition, which opened in 1907 with a capacity of 16,400 seats. Guinlock also designed the Government Building (now Mediaeval Times), Horticultural Building, Music Building, and the Fire Hall and Police Station. In 1912, the name of the fair was changed to the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE). During the ensuing years, many of the grandstand stage shows were historical pageants—the “Burning of Rome-Nero,” “Empire Triumphant,” “Dance of the Squaws,” Siege of Lucknow (India) and “The Durbar of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales.” The last historical stage show was “Britannia,” performed in 1941. For almost four decades, the grandstand remained the focal point of the CNE, until it burnt in 1946.

The architects Marani and Morris were hired to design another grandstand, the general contractor being Pigott Construction. It contained 20,600 seats. Facing south, it was 800 feet in length, the height of its roof soaring to 75 feet. As well as stage performances, it featured stock car racing, auto polo, rodeos, track and field events, circuses, concerts, and military extravaganzas such as “The Scottish World Tattoo. However, the most spectacular events were the grandstand shows, the largest ever held in Canada. Over 1500 stage performers were involved for a single performance, as well as a large orchestra.

View of the north facade of the CNE Grandstand in the 1950s. Photo, CNE Archives

Miss Toronto Beauty Pageant in 1951 in the CNE Stadium, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Item 1696.

Queen Elizabeth in the CNE Grandstand in 1957, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, S1057, Item 4989.

The RCMP Musical Ride at the CNE Grandstand in the 1950s, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, S 1057, Item 574.

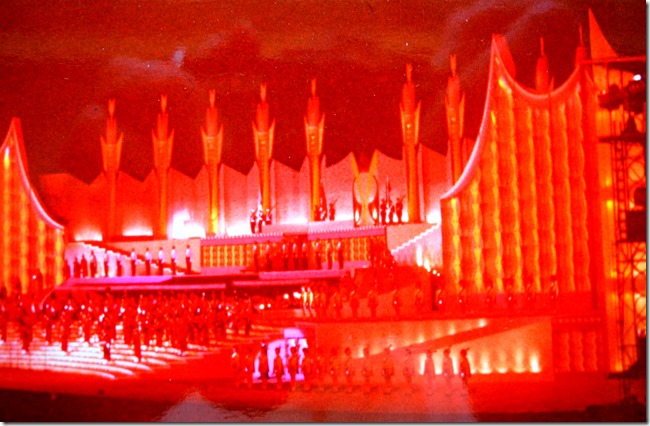

The 1950s and 1960s were the golden age of the CNE Grandstand shows. Shorty after the new grandstand was completed, Leon Leonidoff was hired to produce the shows. He had trained in Canada and after relocating to New York, had a successful career producing performances at the Radio City Music Hall. Employing his connections, he brought the famous “Rockettes” to the grandstand. He also booked famous American stars, along with their supporting casts, costumes and sets. Almost everything was American. In 1948, he hired the famous and outrageous comedy team—Olsen and Johnson. Many citizens of “Toronto the Good” considered them outrageous, complaining that their jokes were crude. The objections voiced about the comedians created so much free publicity that the grandstand was packed every night. The comedy duo continued at the Ex until 1951.

However, many felt that the grandstand shows should feature more Canadian talent and Jack Arthur was hired to fulfill this mandate. American stars continued to be employed as drawing cards, but the remainder of the casts were Canadian. As well, costumes were supplied locally, by Malabar Limited, and the stage sets were all constructed in Toronto. Jack Arthur’s wife, Midge, trained a group of dancers to replace the “Rockettes.” They were named the “Canadettes,” and were advertised as “the longest line of show girls in the world.” Alan and Blanche Lund, a famous Canadian dance team, created the choreography and the immensely talented Howard Cable took over the musical arrangements. Hugh Hand was the mastermind behind the wondrous fireworks displays.

The grandstand shows became spectacles that showcased Canadian talent, featuring Canadian themes. In 1955, Marilyn Bell appeared on the stage, as that year she had successfully swam the English Channel. In 1959, the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway was the theme. In other shows, Max Ferguson portrayed his self-created character “ old Rawhide.” Celia Frank danced with the National Ballet. Concerts included the opera star Teresa Stratas, and Wally Koster, a star of the TV show, “Cross Canada Hit Parade” performed.

Hollywood stars that appeared during the golden years of the CNE Grandstand shows included Bob Hope, Jimmy Durante, Roy Rogers, Dale Evens, Bill Cosby and Danny Kaye. Jack Arthur was also responsible for the creation of an enormous moveable stage, at a cost of $500,000. Jack Arthur retired in 1967, and the last great stage show was in 1968. Its theme was “Sea to Sea—The Iron Miracle,” written by Don Herron.

As the dawn of the 1970s approached, the grandstand shows were no more. However, those who attended them will never forget their grandeur.

This photo of a performance at the CNE Grandstand was taken in 1956. It is another photo that was taken in Kodachrome film with my 35mm Kodak Pony camera.

However, the CNE Grandstand’s fame did not end with the termination of its stage shows. In 1959, the seating capacity was expanded by constructing a south stand and a new section of seats. The facility now possessed 12,472 more seats, and it became the home field for the Toronto Argonauts football team. In 1962, the Grey Cup was held in Toronto, with Hamilton and Winnipeg the participating teams. The conditions on the field were so foggy that it could not be verified that the final touchdown was converted, and the the Tiger-Cats lost the game by a single point. The game became known as the “Fog Bowl.”

In 1975, construction commenced to reconfigure the stadium to accommodate baseball games, the seating capacity now 54,254. In 1976, Toronto received a major league baseball franchise in the East Division of the American League. The team was named the Toronto Blue Jays. They played their first game in the CNE Stadium on April 7, 1977, against the Chicago White Sox. Toronto won the game, the score being 9-5.

However, because the stadium was located close to the lake, weather conditions were unpredictable. Also, there was a desire for a multipurpose stadium. As a result, construction on a new stadium, with a retractable roof, commenced in 1986. The final game played at the CNE was on May 28, 1989, and the Blue Jays moved into the Sky Dome on June 5, 1989. Their first season under the dome was not particularly successful, attracting only 1.7 million fans. However, the Blue Jays went on to win the World Series in 1992 and 1993.

In 1999, the seats at the CNE Stadium were sold and the structure was stripped of anything that might be recycled, only the concrete and steel girders remaining. Explosives were employed to implode the CNE Stadium. A half century of entertainment history ended.

Note. I am grateful for the information contained in: “Once Upon a Century – 100 Year History of the Ex,” by John Robinson, published in 1978 by J. H. Robinson Publishing Limited.

CNE Stadium in the 1980s at the height of its popularity as a baseball venue. Ontario Place is visible in the background.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

A link to view previous posts about the movie houses of Toronto—historic and modern.

A link to view posts that explore Toronto’s Heritage Buildings:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2014/01/02/canadas-cultural-scenetorontos-architectural-heritage/

Recent publication entitled, “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” by the author of this blog. The publication explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Shop, and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

Another book, published by Dundurn Press, containing 80 of Toronto’s old movie theatres will be released in the spring of 2016. It is entitled, “Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again.” It contains over 130 archival photographs.

A second publication, “Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. This book will also be released in the spring of 2016.

![pict0081[1] pict0081[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/pict00811_thumb.jpg)

![Aug. 9, 1928, f1231_it1253[1] Aug. 9, 1928, f1231_it1253[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/aug-9-1928-f1231_it12531_thumb.jpg)

![1950s, CNE archives ad68fb7f-1f51-43c2-aa3b-ecd2a6f1f526[1] 1950s, CNE archives ad68fb7f-1f51-43c2-aa3b-ecd2a6f1f526[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/1950s-cne-archives-ad68fb7f-1f51-43c2-aa3b-ecd2a6f1f5261_thumb.jpg)

![2011713-miss-toronto-1951-es-f1257_s1057_it1696[1] 2011713-miss-toronto-1951-es-f1257_s1057_it1696[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2011713-miss-toronto-1951-es-f1257_s1057_it16961_thumb.jpg)

![2011713-qe2-es-1959-f1257_s1057_it4989[1] 2011713-qe2-es-1959-f1257_s1057_it4989[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2011713-qe2-es-1959-f1257_s1057_it49891_thumb.jpg)

![RCMP Musical Ride, 1950s f1257_s1057_it5746[1] RCMP Musical Ride, 1950s f1257_s1057_it5746[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/rcmp-musical-ride-1950s-f1257_s1057_it57461_thumb.jpg)

![20101011-exhibition-stadium1980s[1] 20101011-exhibition-stadium1980s[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/20101011-exhibition-stadium1980s1_thumb.jpg)

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/cid_e474e4f9-11fc-42c9-aaad-1b66d8521_thumb1.jpg)

Bought back good memories for me,as it is where i saw the beach boys