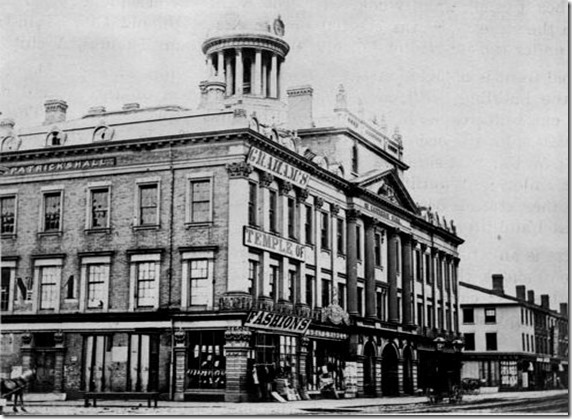

The St. Lawrence Hall in 1890, Ontario Archives, 10021840(1)

Whether a person passes the St. Lawrence Hall on a streetcar, in an automobile, or simply walk to the market on Front Street, the building rarely fails to impress. It is one of the grandest historic structures in the city. The impetus for its construction began across the seas in Britain.

Following the coronation of Queen Victoria, the 1840s became an era when new ideas and a desire to create grand buildings seized the imagination of Britain. The attitude quickly spreading to various cities throughout the Empire. In 1849, in Toronto, a disastrous fire. Beginning in a frame building and stable on George Street, it swept along King Street and the surrounding area. It eventually destroyed almost 15 acres of shops and homes, annihilating a large portion of the city. At its heights, the flames were evident as far away as St. Catharines.

Because it destroyed much of the northern section of the St. Lawrence Market complex, built in 1831, the city realized that they must rebuild the red-brick building on its King Street side. In the spirit of the age, civic politicians decided to rebuild the entire square and include a grand concert hall at its north end.

They hired William Thomas to design the hall. Born in Gloucestershire, England, he trained as an architect and engineer. Shortly after completing his education, he immigrated to Canada with his wife and ten children. In Toronto, he designed St. Michael’s Cathedral and Bishop’s Palace in 1845. In future years, he would create the plans for the Brock Monument at Queenston Heights. However, many consider the St. Lawrence Hall his greatest achievement. It is one of the finest examples of Victorian classicism in Canada.

Thomas was influenced by the Italian Renaissance style. When the Hall was officially opened in 1851, it was admired for its elegance. Its ornate facade was crowned by a cupola that resembled a Roman temple. It contained clocks that faced the four points of the compass. At the front of the building, on the ground level of the four-story structure, were three archways. The central one provided access to the market shops and stalls located within. The city’s coat-of-arms was carved in stone on the front facade, where ornate pilasters separated the arches.

On the second floor, which contained offices, Corinthian pilasters ornamented the facade. The third storey possessed a hall that held 1000 people. The fourth floor was beneath a French Mansard roof, designed to prevent the heavy snow of Canadian winters from piling up on the structure.

The St. Lawrence Hall in 1867, photo Ontario Archives, 10005329 (1)

The north (front) facade of the St Lawrence Hall on King Street, with its three grand archways and detailed stone carvings. A functioning replica of an old gas lamp is on the sidewalk in front of the building. Photo 2011.

North and east facades of the St. Lawrence Hall.

The grand hall on the third floor was enormous for its day. The richly ornamented plaster ceiling soared 34 feet above the wooden floor, its upper windows located in the Mansard roof. The dimensions of the room were 100 feet by 38 feet, 6 inches. A huge crystal chandelier, lit by gas, illuminated the space, along with numerous gas sconces along the walls. A gallery was along the north side of the room to provide extra seating.

Ornate ceiling and crystal chandelier in the grand ballroom, photo taken in 1969.

For over seventy-five years, until replaced by Massey Hall, the St. Lawrence Hall was Toronto’s main cultural centre. The St. Lawrence Hall hosted some of the most important personages of the nineteenth century, including John A. Macdonald and George Brown.

Festival balls, banquets, bazaars, magicians, soirees, and minstrel shows were held within its walls. People gathered for Shakespearean readings and plays, oratorios, operas, and musical concerts. Handel’s Messiah was first performed in the hall in 1857, and though a few of the 200 singers were from outside the city, the remainder were residents. Cycloramas, panoramas, and travelogues delighted the public. Jenny Lind, the famous Swedish singer filled the hall in 1851 on two successive evenings, even though the lowest-price tickets were the exorbitant price of $3.00 per person. Lectures on slavery, spiritualism, immigration, phrenology, and anatomy fascinated the crowds.

View of the third floor area outside the grand hall.

As the population of the city increased, and the city’s boundaries expanded, the area around the St. Lawrence Hall became less accessible. When Massey Hall opened in 1894, the cultural activities of the city gravitated to the new and larger venue on Shuter Street.

In 1967, The St. Lawrence Hall was restored as the city’s centennial project. While the restoration was in progress, the east wall of the building collapsed onto Jarvis Street. However, it was faithfully restored and today the structure appears as elegant as the day it first opened.

The hall shortly after its restoration in 1967.

Rear (south) side of the St. Lawrence Hall, when the north market was under construction.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

To view previous blogs about movie houses of Toronto—historic and modern

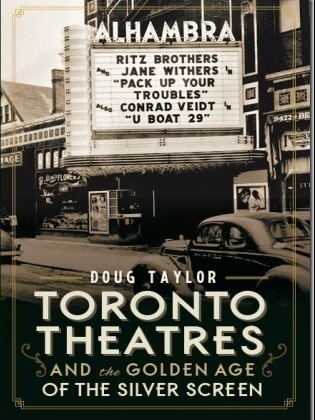

Recent publication entitled “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” by the author of this blog. The publication explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories of the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Store and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791

Theatres Included in the Book:

Chapter One – The Early Years—Nickelodeons and the First Theatres in Toronto

Theatorium (Red Mill) Theatre—Toronto’s First Movie Experience and First Permanent Movie Theatre, Auditorium (Avenue, PIckford), Colonial Theatre (the Bay), the Photodrome, Revue Theatre, Picture Palace (Royal George), Big Nickel (National, Rio), Madison Theatre (Midtown, Capri, Eden, Bloor Cinema, Bloor Street Hot Docs), Theatre Without a Name (Pastime, Prince Edward, Fox)

Chapter Two – The Great Movie Palaces – The End of the Nickelodeons

Loew’s Yonge Street (Elgin/Winter Garden), Shea’s Hippodrome, The Allen (Tivoli), Pantages (Imperial, Imperial Six, Ed Mirvish), Loew’s Uptown

Chapter Three – Smaller Theatres in the pre-1920s and 1920s

Oakwood, Broadway, Carlton on Parliament Street, Victory on Yonge Street (Embassy, Astor, Showcase, Federal, New Yorker, Panasonic), Allan’s Danforth (Century, Titania, Music Hall), Parkdale, Alhambra (Baronet, Eve), St. Clair, Standard (Strand, Victory, Golden Harvest), Palace, Bedford (Park), Hudson (Mount Pleasant), Belsize (Crest, Regent), Runnymede

Chapter Four – Theatres During the 1930s, the Great Depression

Grant ,Hollywood, Oriole (Cinema, International Cinema), Eglinton, Casino, Radio City, Paramount, Scarboro, Paradise (Eve’s Paradise), State (Bloordale), Colony, Bellevue (Lux, Elektra, Lido), Kingsway, Pylon (Royal, Golden Princess), Metro

Chapter Five – Theatres in the 1940s – The Second World War and the Post-War Years

University, Odeon Fairlawn, Vaughan, Odeon Danforth, Glendale, Odeon Hyland, Nortown, Willow, Downtown, Odeon Carlton, Donlands, Biltmore, Odeon Humber, Town Cinema

Chapter Six – The 1950s Theatres

Savoy (Coronet), Westwood

Chapter Seven – Cineplex and Multi-screen Complexes

Cineplex Eaton Centre, Cineplex Odeon Varsity, Scotiabank Cineplex, Dundas Square Cineplex, The Bell Lightbox (TIFF)

![15. c. 1890--I0021879[1] 15. c. 1890--I0021879[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/15-c-1890-i00218791_thumb.jpg)