Shea’s Victoria Theatre in 1955. Photo from the Baldwin Collection, Toronto Reference Library S 1-3287

In the early decades of the 20th century, the name “Shea” was synonymous with theatre excellence. The name referred to two brothers, Jeremiah (Jerry) and Michael Shea, born in St. Catherines, Ontario. Enterprising by nature, they realized the potential of the new entertainment medium,“moving pictures.” In 1903, they rented space at 91 Yonge Street and opened a small theatre, on the east side of the street, between King and Adelaide Streets. The theatre screened silent films, accompanied by vaudeville acts. The vaudeville’s slap-stick routines and comedians had always been popular, but it became obvious that the real attraction was now the “moving picture” shows. Films in this decade were not as lengthy as today, so vaudeville routines were necessary if the Shea brother were to offer a performance that justified the five-cent admission price. The Shea’s Theatre on Yonge Street was an immediate success. With the funds they accumulated, in 1910, they decided to open a larger and grander theatre.

The Shea brothers chose a site at 83 Victoria Street, on the southeast corner of Richmond and Victoria Streets. They engaged the architect Charles James Reid to design their theatre. In 1908, Reid had been appointed the official architect of the Roman Catholic Separate School Board in Toronto, and between the years 1910 and 1920, he designed many school throughout the city. He was also the architect of the York Theatre on Yonge Street, north of Bloor. Reid chose an unadorned facade for the new Shea’s theatre, with an elaborate cornice and beneath it, modillions that resembled large dentils. The design of the facade facing Victoria Street was symmetrical, except for the ground floor, where there was a door to the right of the entrance. A plain rectangular canopy over the entrance protected patrons from inclement weather as they alighted from cabs and carriages or entered on foot.

Determined to offer the best vaudeville and legitimate theatre in the city, the Shea brothers competed with the Princess and Royal Alexandra Theatres on King Street. In some respects this was not accurate, as the latter two theatres did not offer vaudeville. However, the Shea brothers did compete for popular touring plays. Shea’s Victoria, which was simply referred to as the Victoria, contained two balconies, the combined seating capacity approximately 1800 seats, of which 700 were on the ground-floor level. The projection booth was at the rear of the second balcony. A 1909 issue of Construction Magazine, a highly respected periodical, gave the theatre a positive review for its architectural design.

Despite the increasing popularity of films, the Victoria continued to offer live theatre. Barry Jones, a famous British film star in the 1920s, performed at the Victoria in 1926. In later years, Jones played Aristotle in the film “Alexander the Great.” This movie was released 1956, Richard Burton playing the role of Alexander. Jones retained fond memories of the Victoria, but stated that the Royal Alexandra was the finest theatre of them all. On April 16, 1936, “Ten Minute Alibi,” a smash hit from London’s West End, where it had played for two years, opened at the Victoria. It was one of many road shows performed at the theatre. These shows usually played between one and eight weeks, depending on ticket sales. Eventually, Famous Players purchased the theatre.

When vaudeville died, the Victoria closed. Though empty, it was employed for special events and for charity fund-raisers, such as those for Crippled Children’s. Jewish stage plays were also performed in the theatre. Since it was not in continuous use, during the early years of World War II, big-name theatrical acts rehearsed at the Victoria prior to being shipped overseas to entertain the troops.

About the year 1944, Famous Players submitted a request for a license to convert the theatre exclusively for movies. The license was granted on December 3, 1945, the capacity listed as 1896 seats. However, difficulties with the licensing authorities continued as the top balcony did not contain proper exists, the aisles blocking the escape route. The authorities ordered the upper balcony closed. In 1947, with a reduction in seating capacity to 1260, another licence was issued. The same year, a candy bar was installed. During the summer of 1949, the theatre closed for renovations. It received new seating and a new floor in the auditorium. These were completed by January 1950.

The newly renovated Victoria continued as one of Toronto’s largest movie theatres. However, as attendance declined, the theatre’s size made it difficult to fill. No longer profitable, it was demolished in April 1956 by the wrecking company of A. Badali, and the site became a parking lot. Another of the city’s great theatres of yesteryears disappeared from the scene.

The auditorium of the Victoria, photo Ontario Archives.

Lobby of the Victoria c. 1946, photo Ontario Archives.

Auditorium of the Victoria, the organ and organist visible on the left-hand side of the stage. Photo Toronto Archives, Series 1278 File 166.

The Victoria c. 1946. The facade facing Victoria Street contains the marquee, but the canopy has been removed. The facade with the fire escape faced Richmond.

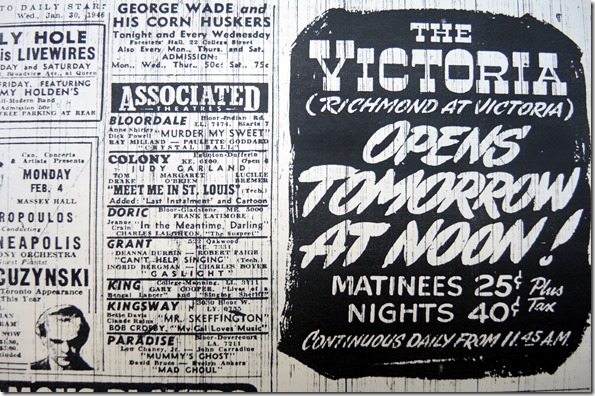

Theatre ad for the Victoria published January 30, 1946.

This view gazes west along Richmond Street c. 1946. In the distance the Tivoli Theatre is visible. It was originally the Allen Theatre.

View gazing west along Richmond Street, the east wall of the theatre demolished to expose the auditorium. The remains of the two balconies are visible. Photo, City of Toronto Archives, the Salmon Collection.

The following article was written by Herbert Whittaker and appeared in the Globe and Mail on April 7, 1956. A copy of it is in the Toronto Archives, Series 1278, File 166.

I paused outside the Victoria Theatre the other day and looked at the billboard. Somebody with a sense of style and maybe of irony, had printed, DEMOLITION by A. Badali. I pushed open the door and stepped inside. Mr. Badali’s show lived up to its name. What I saw without a doubt, the most devastating, shattering, heart-rendering performance the Victoria had ever witnessed. Mr. Badali was bringing down the house.

The shape of the auditorium was still there, clouded but not concealed by the debris. The proscenium arch still stood intact, although all beyond it had crumpled under the wrecker’s attacks. But it was not hard to recall the days of the Victoria’s youth, not hard to imagine these areas filled up with good citizens of an older Toronto and that beyond the arch filled in again with brightness and colour, and the actors moving about their business of fascinating.

I came back to the office and suggested that a photo should be taken immediately, if we were to catch a last look at the theatre. The editor agreed that it might be of interest to a great many people. I have reason to believe it has. In fact, one playgoer had the sound of tears in his voice when he spoke about it on the telephone.

Then I went off to meet Barry Jones, the British actor who was in town to talk about the forthcoming film of Alexander the Great, in which he plays Aristotle to Richard Burton’s Alexander.

It was not too hard to get Mr. Jones off the subject of Alexander the Great onto that of Toronto theatres, because he has a very special affection for this town. Although widely known as a British star, through films and plays, Mr. Jones had only been in theatre 18 months when he made his first appearance here, and has had his most satisfactory experiences here during his many subsequent appearances.

“It was in 1923,” Mr. Jones recalled warmly, “when I first came to Toronto with the Cameron Mathews stock company at the Regent Theatre. It’s a parking lot now,” he added morosely. “The Comedie Theatre, which had been called the Gaiety before that was the next theatre I worked in,” he went on. “That was in 1925. It stands where the Victory Building now stands, I think. Then, there was the Uptown. That was where the Glaser Company played. I remember O. P. Heggie was in the cast, a fine actor. That was in 1926.”And Mr. Jones had played at the Victoria in 1926. This same Victoria that now entertains the wrecker Badli.

Later, Mr. Jones was to go on to greater experiences at the Royal Alexandra. It was here that his famous tours with Maurice Colbourne began, and here that they drew their biggest and best audiences, Mr. Jones recalled fondly. Those plays were history-making, as being the last of a long line of theatrical treats to come from England. Robert Sherwood’s “The Queen’s Husband,” Briedie’s “Tobias and the Angel,” Mr. Colbourne’s own “Charles I”, Shaw’s “John Bull’s Other Island” and hot from the headlines, Shaw’s “Geneva Geneva” played in the stormy year of 1939, completed in memorable cycle, and a theatrical era.

There are, then, reasons for Mr. Jones’ affection for Toronto as a theatrical centre, and particularly for the Royal Alexandra. He upholds the “Royal Alex” as the best theatre he has ever played in, anywhere. “If the Royal Alexandra was ever ton down,” said Mr. Jones threateningly, I should never return to Toronto. Don’t let anything happen to it. I smiled sympathetically, pleased with his interest. Then the echo of names came back to me—the Regent Theatre, the Comedie, the Uptown, the Old Princess, the Victoria—I stopped smiling.

I thought of the Victoria at this moment being razed to make a parking lot. I wondered if someday, somebody else would be naming theatres which no longer existed—“and then there was the Royal Alexandra and the Crest on Mount Pleasant and the Avenue, where Spring Thaw used to play. A city is bound together by its happy hours, by the memories of exciting nights spend in mutual laughter or tears at a mimic show. How many happy hours of the past are made anchorless by the demolition of the Victoria?

Walking around the side of the shattered building, I had seen a curious sight. Against one wall, as a tarpaulin, the wreckers were using a bit of old canvas they had found in the wreckage found backstage. But it wasn’t any old bit of canvas. It had once been a backdrop, on it still was the painted scene—a garden, in the Maxfield Parrish tradition, with a lovely blue vista. The old painted cloth, which once created illusions under the stage lights, now hung tawdrily in the spring sunshine, flapping idly. It might be the banner of a losing cause, so disconsolate it looked. But as I looked at it, it seemed to brighten into a gallant flag.

“Let them tear down the Victoria. Let them put a parking lot there. What I stand for is glory and colour and communication, and laughter and tears, and thrilling voices sounding out and the roar of applause to follow. What will the parking lot leave behind it, when automobiles are obsolete and gasoline outmoded?”

Mr. Whittaker was unaware that of the over 150 theatres that existed when he wrote the article, all but a handful of them would disappear.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

To view previous blogs about movie houses of Toronto—historic and modern

Recent publication entitled “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” by the author of this blog. The publication explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories of the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Store and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791

Theatres Included in the Book:

Chapter One – The Early Years—Nickelodeons and the First Theatres in Toronto

Theatorium (Red Mill) Theatre—Toronto’s First Movie Experience and First Permanent Movie Theatre, Auditorium (Avenue, PIckford), Colonial Theatre (the Bay), the Photodome, Revue Theatre, Picture Palace (Royal George), Big Nickel (National, Rio), Madison Theatre (Midtown, Capri, Eden, Bloor Cinema, Bloor Street Hot Docs), Theatre Without a Name (Pastime, Prince Edward, Fox)

Chapter Two – The Great Movie Palaces – The End of the Nickelodeons

Loew’s Yonge Street (Elgin/Winter Garden), Shea’s Hippodrome, The Allen (Tivoli), Pantages (Imperial, Imperial Six, Ed Mirvish), Loew’s Uptown

Chapter Three – Smaller Theatres in the pre-1920s and 1920s

Oakwood, Broadway, Carlton on Parliament Street, Victory on Yonge Street (Embassy, Astor, Showcase, Federal, New Yorker, Panasonic), Allan’s Danforth (Century, Titania, Music Hall), Parkdale, Alhambra (Baronet, Eve), St. Clair, Standard (Strand, Victory, Golden Harvest), Palace, Bedford (Park), Hudson (Mount Pleasant), Belsize (Crest, Regent), Runnymede

Chapter Four – Theatres During the 1930s, the Great Depression

Grant ,Hollywood, Oriole (Cinema, International Cinema), Eglinton, Casino, Radio City, Paramount, Scarboro, Paradise (Eve’s Paradise), State (Bloordale), Colony, Bellevue (Lux, Elektra, Lido), Kingsway, Pylon (Royal, Golden Princess), Metro

Chapter Five – Theatres in the 1940s – The Second World War and the Post-War Years

University, Odeon Fairlawn, Vaughan, Odeon Danforth, Glendale, Odeon Hyland, Nortown, Willow, Downtown, Odeon Carlton, Donlands, Biltmore, Odeon Humber, Town Cinema

Chapter Six – The 1950s Theatres

Savoy (Coronet), Westwood

Chapter Seven – Cineplex and Multi-screen Complexes

Cineplex Eaton Centre, Cineplex Odeon Varsity, Scotiabank Cineplex, Dundas Square Cineplex, The Bell Lightbox (TIFF)

![Balwin Coll., TRL S 1-3287 in 1955 pictures-r-5617[1] Balwin Coll., TRL S 1-3287 in 1955 pictures-r-5617[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/balwin-coll-trl-s-1-3287-in-1955-pictures-r-56171_thumb.jpg)

![May 6, 1956, Toro. Ref. Lob, Salmon Collec. pictures-r-5615[1] May 6, 1956, Toro. Ref. Lob, Salmon Collec. pictures-r-5615[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/may-6-1956-toro-ref-lob-salmon-collec-pictures-r-56151_thumb.jpg)

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/cid_e474e4f9-11fc-42c9-aaad-1b66d8521_thumb1.jpg)

One thought on “Toronto’s old Shea’s Victoria Theatre”