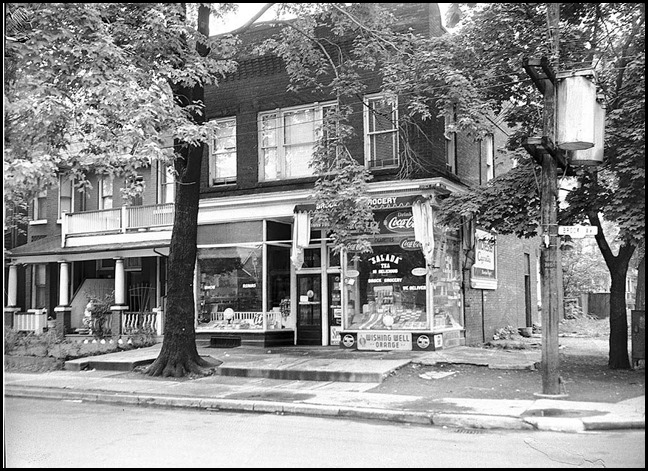

Patoff Grocery at 391 Brock Avenue; to the left of it is Smythe Variety Store. Patoff’s was operated by Sam Patoff. Prior to Sam operating the store, it was called Supreme Store (see flyer below) This information was provided by Leo Darmitz, whose father operated a store at 395 Brock. Leo’s father did not own his store when the above photo was taken, but he states that it looked exactly the same. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, S. 1057, Item 7643

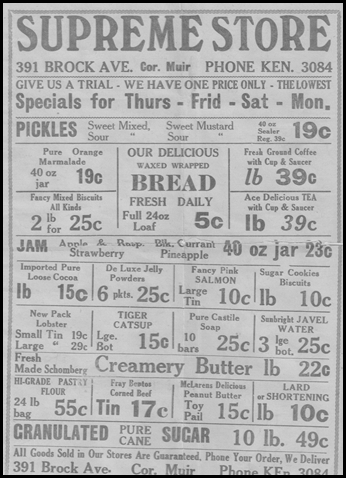

Copy of a 1929 flyer from the Supreme Store at 391 Brock Avenue, when bread was 5 cents a loaf and butter was 22 cents (flyer courtesy of Leo Darmitz).

Toronto is often referred to as a “city of villages.” The Greek Village on Danforth Avenue and the city’s three Chinatowns are favourites of many Torontonians. There are two Italian “villages”— one on St. Clair West and another on College Street. The latter is also referred to as Little Portugal as many Portuguese reside in the area. The Korean Village is on Bloor Street near Christie and the Polish Village on Roncesvalles Avenue. There are many other areas within the city that are referred to as villages, as they share a common ethnicity. However, prior to the 1950s, before Toronto became multicultural, the city was also composed of villages, but they were not defined by ethnicity.

When I was a boy in the 1940s, our street was akin to a village. In this decade, society was not as transitory as today. Most people bought homes only once in a lifetime. They raised their children in them and remained in the same house after their children had grown and departed. Similarly, it was not uncommon for people to be employed for their entire lives by only one company, beginning when they were young and retiring from the same firm. Unlike today, it was rare for people to be suddenly transferred to cities thousands of miles away, and then after a few years, transferred once more. People put down deep roots in their communities, where they knew their neighbours and shared their concerns.

Frequently, teachers in schools educated the children of parents whom they had taught when they were kids. Married women were not allowed to work as teachers; if they married, they were forced to resign. This meant that female teachers did not take time off to have children and raise them, so the staffs of schools changed little from year to year. The community knew the names of the teachers within their local school, so the teachers were sometimes the topic of discussions in the corner stores.

Our street was no exception. Most families had resided there for many years, a few of them for more than a generation. It was ethnically cohesive, as almost everyone traced their ancestry to the British Isles, as did most of Torontonians. There were also quite a few Newfoundlanders in our neighbourhood, who had immigrated before their native isle joined Canada, in 1949. On our street, when a neighbour died, their passing was mourned by everyone. People offered assistance, which often consisted of food, and grieved with the family that had lost a loved one. Similarly, if a neighbour moved away, which was not often, everyone on the street wished them well, helped them move, and shed a tear as they departed. At the end of of World War II in 1945, as the soldiers returned from overseas, each homecoming was a “village” celebration, not a one-family event. The same was true after the Korean Conflict.

Similar to a rural village, we were aware when we departed the boundaries of our “street-village.” We no longer recognized the people passing on the sidewalk. My family knew almost everyone by name for about a quarter of a mile to the north or south of our house. Only one family on our street owned a car, a black bustle-back 1938 Chevrolet. In the 1940s, everyone walked or boarded a streetcar to go to church or attend a movie theatre. We also walked to the local shops, which were an integral part of our village. Visits to them always entailed meeting neighbours and stopping to chat. When I was a boy, older people greeted me and enquired about my studies at school. I secretly rated adults by the quality of the treats they “shelled-out” on Halloween, or by the amount of the tip they gave me at Christmas time, since I was their paperboy who delivered their daily newspapers.

However, the most important of all the shops were the “corner stores.” We visited them every day, sometimes more than once, as opposed to the churches and theatres that we attended once a week. The “corner stores” varied. They might be a drug store, a variety store, or a grocery store. If you were lucky, your street contained all three, or at least two of these types. Our neighbourhood had a drug store and a grocery store.

Corner stores adjusted their merchandise to accommodate the neighbourhoods. If a grocery store did not sell ice cream, the drug store filled the void. Often, corner stores sold everything except prescriptions, unless it was a drug store. Sometimes, they even stocked items that would normally be found in hardware stores. As a child, I purchased penny candy in them. The endless boxes of sweets were truly a sight to behold, the licorice cigars being my favourite. Today, the only place I know where I am able to see a similar array of candies is in the Kensington Market, at Casa Acoreana, at 297 Augusta Avenue. In this shop, the candies are contained in large bottles. However, there is nothing available for a penny, even the penny now having disappeared into history. (note: since writing this post, Casa Acoreana has closed).

On hot summer days, at the corner drug store, we bought orange Popsicles for 5 cents, or a Mello Roll ice cream cone for 6 cents. There were only three flavours of cones—vanilla, strawberry and chocolate. A single serving of a Mello Roll ice cream was wrapped in white, wax-coated paper that was peeled back to allow it to be inserted into the cone. This allowed the store owner to place the ice cream in the cone without touching it. Using a scoop to form a ball of ice cream and then placing it in a cone had not yet appeared on the scene. Sprinkles on top of cones only appeared after they were scooped from large containers.

My family sometimes purchased a “brick” of ice cream, on a humid summer evening. An ice cream brick was rectangular in shape, similar to a small building brick. Our favourite flavour was Neapolitan that contained vanilla, strawberry and chocolate ice cream, with a strip of orange in the centre that was similar in texture and taste to an orange Popsicle. Sometimes my dad bought a quart bottle of “Wilson’s Golden Amber Ginger Ale” to make an ice cream float. “Kik Cola” was another favourite soda pop used for this purpose. Sitting on the veranda after dark on a steamy August evening, observing the passing scene on the street, and sipping on an ice cream float or consuming a slice of ice cream cut from a brick, was our definition of heaven.

Our neighbourhood grocery store was where my family purchased our daily needs, though every Saturday my mother went to a small Dominion Store that was a ten-minute walk from our house. Our local grocery store was owned by two brothers, one of whom was the butcher. He never came out from behind the counter during working hours, and some kid started a rumour that the reason was that he did not wear any trousers. Kids giggled whenever they observed him in the store, while trying to determine if the the rumour were true. No child ever solved the mystery.

The corner store was where my mother purchased butter, sugar, Jell-O powder, and meat. All these items were rationed during the war years, so she handed over government-issued coupons whenever she purchased them. In autumn, outside the store, the rich scent of the purple Concord grapes from Niagara filled the air. They were employed to make jelly to spread on toast on cold winter mornings. Bushels of Ontario sweet corn were stacked alongside baskets of apples, pears, peaches and plums, all adding to the colourful display. My mother bought generous quantities of the fruits to fill her preserving jars. These were stored in our root cellar during the winter months. Similarly, each autumn my father brought home a burlap sack of potatoes and another of onions. These were also stored in the root cellar for winter meals. Imported fruits and vegetables were not available in the 1940s so my mother’s preserves and canned fruit sufficed. As well, many foods were in short supply because of the war.

The corner store was where the news of the “street-village” was disseminated, along with generous portions of gossip. Not all the comments were kind. It was a decade when divorced women, as well as those who had children out of wedlock, were considered shameful. Neighbours who did not properly sweep the sidewalks in front of their houses or whose laundry on the clothesline did not appear clean, were criticized. Those who did not attend any church or worship at a synagogue also received a good share of criticism.

However, corner stores were also where people shared their problems and supported each other. The harsh realities of life were softened by discussing them with neighbours. Health difficulties, problems providing food for the table, loneliness as sons or a husband were overseas, as well as day-to-day stresses were ameliorated by a few sympathetic words spoken at corner stores.

Politics, soap operas on the radio, Hollywood hairstyles, movie stars, and the current films at the local theatre, were all discussed. Another favourite of the gossip mills was the antics of a local Romeo or a woman of “loose morals.” This term encompassed a myriad of mostly trivial nefarious behaviour. Most streets possessed at least one child who spoke about the visits of an “Uncle Harry” on Wednesday nights when their father worked late. The 1940s was a decade when coal, bread and milk were delivered directly to homes, often by horse-drawn wagons. A handsome delivery man elicited many remarks, as well as a few knowing smiles. A child that was better looking than either of his parents was jokingly referred to as another product delivered by the milk or bread man.

News from the war front was usually avoided in the corner shops. Almost every family was touched by the war, as they had a relative, friend or neighbour serving overseas. Discussing the latest battles or casualty reports added to people’s fears. However, though not often discussed, the war remained a concern that lingered beneath the surface of the lives of everyone.

If people wished to discuss conflict with a fierce opponent, a recent argument with a cantankerous mother-in-law sufficed. She did not seem quite so bad after a few jokes about her dentures, a recently purchased girdle or a ridiculous new chapeau. A bit of laughter healed many wounds and kept the demons of war at bay. The mundane topics at the corner store, along with those that were humorous and tragic, reflected the daily life of the community. I do not believe that texting in the modern era fulfills the same role. The personal touch is missing as there is no visual contact, and though Skype is not a particularly a good substitute, WhatsApp and Facetime are quite good.

After World War II ended, a flood of immigrants and refugees arrived in Toronto. Neighbourhoods began to change as Torontonians relocated to the suburbs. Immigrants purchased their homes in the older neighbourhoods as they were less expensive, unlike today when downtown homes command an outrageous price. During the 1950s, multi-cultural Toronto was on the horizon, with an influx of new customs and different foods. Life in Toronto became more transient. Immigrants did not stay in the older areas for long. As they prospered, they too relocated. The village feeling of neighbourhoods diminished, although ethnic enclaves continued many of the traditions of Toronto of old.

I miss the Toronto of old. Social media and smart phones have replaced conversations in cafes, restaurants and neighbourhoods. However, I believe that the city is now far more exciting, thanks in part to the immigrants who have made Toronto their home.

Corner store operated by the father of Mr. Darmitz at 395 Brock avenue. Toronto Achives, Fonds 1257, Series1057, item 7646 . Photo was brought to my attention by Leo Darmitz who located them in the archives and sent me a copy.

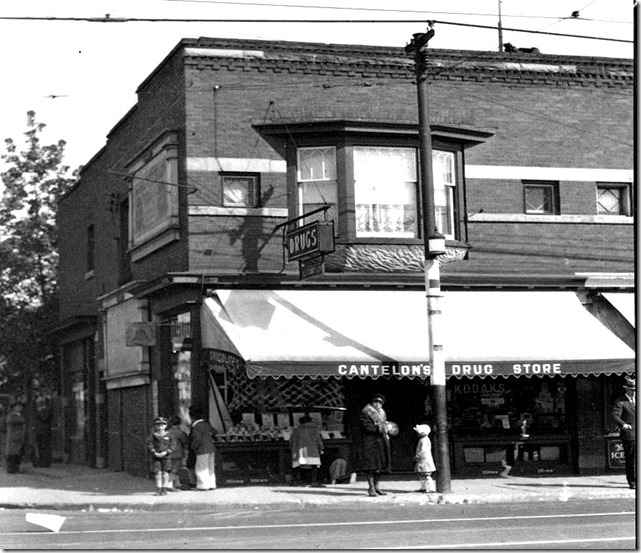

A corner drug store, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1266. Item 18008.

Corner store at Davenport and Dupont Street, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231, Item 2080.

Store at Dundas and Ontario Streets, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1526, Fl. 0009, Item 0025.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

Books by the Author

“ Lost Toronto”—employing detailed archival photographs, this recaptures the city’s lost theatres, sporting venues, bars, restaurants and shops. The richly illustrated book brings some of Toronto’s most remarkable buildings and much-loved venues back to life. From the loss of John Strachan’s Bishop’s Palace in 1890 to the scrapping of the S. S. Cayuga in 1960 and the closure of the HMV Superstore in 2017, these pages cover more than 150 years of the city’s built heritage to reveal a Toronto that once was.

“Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who personally experienced these grand old movie houses. To place an order for this book, published by History Press:

Book also available in most book stores such as Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox and AGO Book Shop. (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2) and may also be purchased on Amazon.com.

“Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again” explores 81 theatres. It contains over 125 archival photographs, with interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating histories. Note: an article on this book was published in Toronto Life Magazine, October 2016 issue.

For a link to the article published by Toronto Life Magazine: torontolife.com/…/photos-old-cinemas-doug–taylor–toronto-local-movie-theatres-of-y…

The book is available at local book stores throughout Toronto or for a link to order this book: https://www.dundurn.com/books/Torontos-Local-Movie-Theatres-Yesteryear

“Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. It contains archival and modern photos that allow readers to compare scenes and discover how they have changed over the decades. Note: a review of this book was published in Spacing Magazine, October 2016. For a link to this review:

spacing.ca/toronto/2016/09/02/reading-list-toronto-then-and-now/

For further information on ordering this book, follow the link to Amazon.com here or contact the publisher directly by the link below:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21

![Davenport and Dupont, 1930 f1231_it2080[1] Davenport and Dupont, 1930 f1231_it2080[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/davenport-and-dupont-1930-f1231_it20801_thumb.jpg)

![DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[2] DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/dscn2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_2_thumb.jpg)

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/cid_e474e4f9-11fc-42c9-aaad-1b66d8521_thumb.jpg)

![image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1] image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb1_thumb.png)

Patoff’s grocery store was at 391 Brock Avenue. It was operated by Sam Patoff. Prior to Sam operating the store, it was called SUPREME STORE. I have an advertising flyer from the store from 1929. Bread was 5 cents a loaf and butter was 22 cents. My father operated another grocery store just across the street at 395 Brock.

Great article on corner stores as they still were in the 40’s & 50’s. I grew up at Queen/Bathurst Sts. late 40’s to 50’s and that is exactly what our corner stores were like (often run by mom & pop & kids). Some gave credit if they knew parents were good for it and marked items in large book behind the counter. Most, but not all, closed on Sundays. Everybody kid bought cigarettes for their parents or uncles. Silverwoods Dairy, Canada Bread, Simcoe Ice, the Sheeney Man (used clothes/metal/junk, etc.), still had horse-drawn carts into the 50’s. Knife sharpener walked pulling his wheel cart. Kids played on the street (Richmond say) because there wasn’t much traffic especially on Sundays. Families knew each other’s proclivities & activities but most lived and let live unless they were considered dangerous. Kids looked out for one another, especially younger siblings. The 60’s brought enormous change with European immigration and wonderful easing of conservative restrictions in Toronto. Still it does seem to have been a pretty good time to be a kid.