The south facade of the Old Registry Building in 1955, photo from the Toronto Public Library, r- 5673

The beginning of the 20th century delivered a spirit of optimism to Toronto, along with a desire for new civic development. Among the districts being considered for transformation was the district to the northwest of the City Hall (today’s Old City Hall). New buildings had already been erected in the area—an extension to the north side of Osgoode Hall, the Armouries on east side of University Avenue, T. Eaton Company’s expansion, and the Toronto General Hospital’s new buildings on its north side. Adding to the impetus for new development was the deterioration of the houses in the area, many of which required demolition. However, there was no overall plan to accomplish the city’s aims.

In 1911, a design was finally proposed by John M. Lyle, who had already designed the Royal Alexandra Theatre and later would be the architect for Union Station. The plan Lyle put forward in 1911 suggested that a grand avenue be built, named Federal Avenue, which would extend northward from the new Union Station (under construction) to Queen Street. The avenue’s northern terminus would be a short distance to the east of Osgoode Hall. It would create a grand vista for both Osgoode Hall and Union Station. Federal Avenue would be located between Bay Street and University Avenue, a short distance to the east of today’s York Street.

Federal Avenue would lead to a new civic square that would occupy two city blocks, bounded by University Avenue and Queen, Bay, and Agnes Streets. The latter street is today Dundas Street. The square would contain impressive civic buildings and a large public garden. It was envisioned that the civic offices would accommodate the needs of the rapidly expanding city.

Map of John Lyle’s plan of 1911 for downtown Toronto between Front and Agnes Street (Dundas Street), showing the proposed Federal Avenue that would begin at Union Station and extend northward to Queen Street. Osgoode Hall, the proposed public gardens, and University Avenue are shown on the map. On the right-hand side of the map is Bay Street, and University Avenue is on the left-hand side. In this decade, University Avenue ended at Queen Street. It was not extended southward to Front until the 1930s.

The first civic structure planned for the square was the Registry Office, resulting in City Council authorizing an architectural competition. The guidelines stated that any designs submitted were to be restricted to the Beaux-Arts and Classical styles. The practical needs of the Registry Office were also listed. The structure must contain two wings, one for the east end of the city and another for the west. The two wings were to be connected by a grand entrance hall and a stairwell. Each wing must have its own research areas, library, and public space. Despite these pre-determined features, all the designs submitted between the year 1909-1910 were large rectangular structures with exceedingly large porticos (porches) across the south facade.

After considerable consideration, the designs of Charles S. Cobb were voted as being the most acceptable. Cobb’s architectural plans reflected the Roman Classical style. The eight massive stone columns supporting the portico were Ionic (scrolled capitals), the roof above them plain with unornamented, parallel lines. The walls were of smooth masonry, creating the appearance of an impressive Roman temple. In the interior, the wide entrance hall separating the east and west sections was lit by a skylight on the roof. The walls inside the rooms were faced with Champville marble from France, the floors of Tennessee marble, baseboards of Botticino marble from Italy, and the windowsills and countertops of marble shipped from near Regina.

Construction on the Registry Office commenced in 1914 and despite the interruptions caused by World War 1, was completed in 1917. However, funds to build the other structures and the garden planned for Lyle’s square never materialized. The Registry Office appeared rather lonesome, with no other buildings to provide it with context. When the Great Depression began in 1929, any hope of redeveloping the land surrounding the Registry Office disappeared.

In 1946, after the World War 11 ended, the city entered into another period of prosperity, which spurred redevelopment. Once more, City Council began considering plans to create a grand square near the Registry Office. The square was to include a new city hall to replace the building that had opened in 1899 (now the Old City Hall). A competition for designs for the new civic building was inaugurated in 1958. Unfortunately, none of the proffered plans included the Registry Office. The design by Viljo Revell was eventually selected for the New City Hall, its modern lines and shapes completely out of sync with the Registry Office’s classical style.

After construction commenced on Toronto’s New City Hall, many other buildings near the Registry Office were demolished, allowing it to be visible from Queen Street for the first time in several decades. However, in 1964, the Registry Office was also demolished to allow the New City Hall to be completed. It opened in 1965 with much fanfare and celebration, a unique structure that attracted world attention. Today, the site of the Registry Office of 1914 is to the west and south the New City Hall, a short distance north of Queen Street.

It could be argued that it was impossible to prevent the demolition of the Registry Office, since it was too costly to maintain and very difficult to recycle for other purposes. I do not accept this view. If the city council had instructed Viljo Revell to include the building in the plans for the new City Hall, Nathan Phillips Square would today still have a new modern City Hall, but also a contrasting structure from the past, on its west side, to balance the square. It would have been possible reposition the New City Hall to face west. Because the old City Hall was to the east of the square, it too should also have been included in the overall plan. It is a pity that this was never considered. The 1960s was an era dedicated to “progress,” which to most civic officials meant demolishing the accomplishments of former generations.

Other city’s have blended the old and the new to achieve astounding results. The Registry Office could have been renovated to house a Toronto Museum (we still do not have one), Toronto Archives, Public Library, or a multi-purpose cultural centre that included a theatre. However, instead, Toronto’s past was deemed irrelevant and relegated to the trash heap. Unfortunately, the type of narrow-minded thinking has doomed many historically important heritage buildings. This type of thinking still remains today among some city councillors.

Sources: William Dendy’s “Lost Toronto”— www.examiner.com

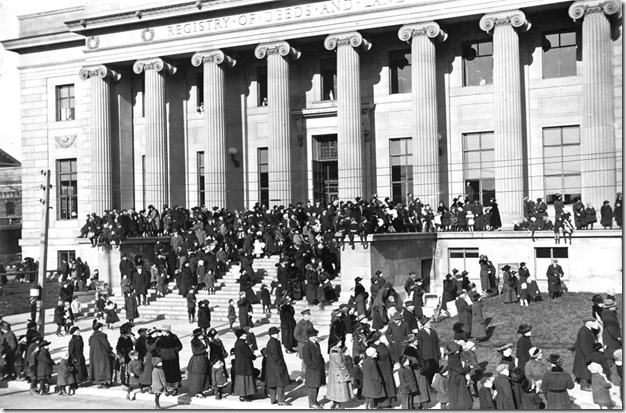

View of crowds in front of the Registry Office in 1913. The people are all facing east, as if they are observing something. Photo from the Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 122

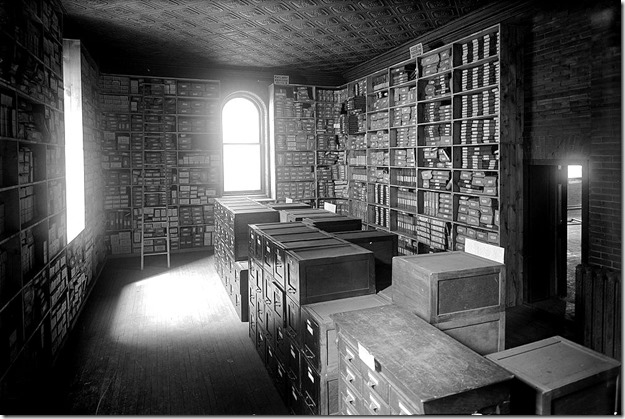

A storeroom in the Registry Office on July 31, 1925. Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, Series 372, SS 41.

View from the Old City Hall clock tower on August 27, 1925. Behind the Registry Office (in the foreground) is the old Armouries on University Avenue (now demolished).

South facade of the Registry Office, facing Albert Street. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1548, S 0393, Item 0023.

View of the Registry Office in 1958. The east side of Osgoode Hall is to the left of it, and between the two structures the old Armouries on University Avenue are visible. The empty space in the foreground is where the land has been cleared to build Nathan Phillips Square. Photo from the Toronto Public Library, r-1-13.

Undated photo of the Registry Office. It appears as if the building is empty, awaiting demolition. Toronto Archives, Fonds 124, Item 0047.

The Metropolitan Library in New York City. Would anyone consider demolishing a building such as this? The Registry Office compares favourably in size and design with the New York structure.

The New City Hall under construction on June 22, 1964, the old Registry Office to the left (west) of it. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1268, Item 0462.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

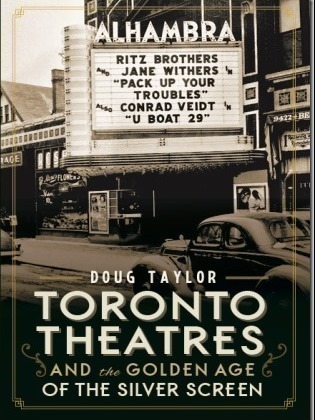

The publication entitled, “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” was written by the author of this blog. It explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Shop, and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

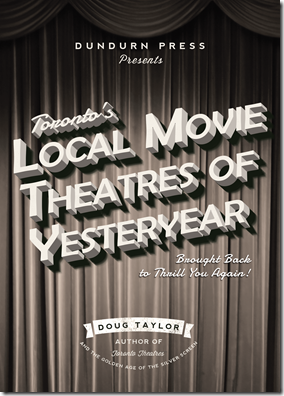

Another book, published by Dundurn Press, containing 80 of Toronto’s former movie theatres will be released in June, 2016. It is entitled, “Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again.” It contains over 125 archival photographs and relates interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating history.

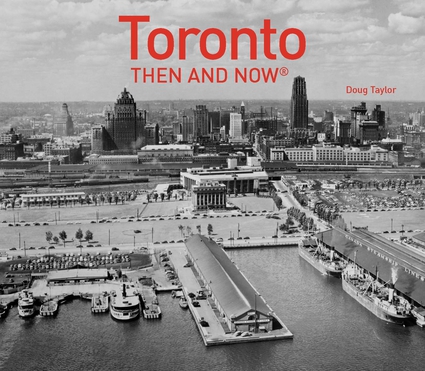

Another publication, “Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. This book will be released on June 1, 2016. For further information follow the link to Amazon.com here or to contact the publisher directly:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21.

![photo 1955, blg. 1917-64 pictures-r-5673[1] photo 1955, blg. 1917-64 pictures-r-5673[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/photo-1955-blg-1917-64-pictures-r-56731_thumb.jpg)

![fedave[1] fedave[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fedave1_thumb.jpg)

![From City_Hall_clock_tower[, Fonds 1548, S393, It.19979, Aug. 27, 1925. 1] From City_Hall_clock_tower[, Fonds 1548, S393, It.19979, Aug. 27, 1925. 1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/from-city_hall_clock_tower-fonds-1548-s393-it-19979-aug-27-1925-1_thumb.jpg)

![pre-1940-- f1548_s0393_it0023[1] pre-1940-- f1548_s0393_it0023[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/pre-1940-f1548_s0393_it00231_thumb.jpg)

![TRL, 1958 cityhall-a-r1-13[1] TRL, 1958 cityhall-a-r1-13[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/trl-1958-cityhall-a-r1-131_thumb.jpg)

![Tor. Archives, Fonds 124, f.124, F001, id.0047 resistry[1] Tor. Archives, Fonds 124, f.124, F001, id.0047 resistry[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/tor-archives-fonds-124-f-124-f001-id-0047-resistry1_thumb.jpg)

![June 22, 1964. f1268_it0462[1] June 22, 1964. f1268_it0462[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/june-22-1964-f1268_it04621_thumb.jpg)