Spadina House at 285 Spadina Road in August 2014. The view gazes northeast toward the west (left-hand) and the south facades. On the south (right-hand) side is a large second-storey veranda that has a commanding view of the city below the hill. On the first floor, below the veranda, is the glassed-in “palm room,” containing a winter garden.

Spadina House (and museum), on the brow of the hill that overlooks Davenport Road, is one of the most historic properties in Toronto. Exploring the house on a guided tour provides an intimate look into the life of the Austin family. The Austins moved into the home in 1866 and a member of the family remained in residence until 1982. Today, it mainly features the life of the Austins during the 1920s. In the warm months, visiting it also provides an opportunity to explore one of Toronto’s finest, restored Victorian gardens.

The story of the property where Spadina House is situated begins in the final years of the 18th century, when Toronto was the small colonial town of York. In 1798, the land where the house is now located was part of a 200-acre lot acquired by William Willcocks. In 1803, Willcock’s daughter, Phoebe, married William W. Baldwin, an Irish immigrant. Phoebe inherited the Baldwin property from her father’s first cousin, Elizabeth Russell, the sister of Peter Russell. Elizabeth suffered from mental illness during her later years, but did not pass away until 1822. Thus, William and Phoebe Baldwin must have gained control of the property prior to her death.

Because William Baldwin intended to erect a grand home on the land, in 1813, he commenced building an impressive roadway, 132 feet wide and a mile and a half in length, as a grand carriageway to the dwelling. The roadway led from the bottom of the hill (Davenport Road), south to Queen Street. South of Queen was Brock Street, which was connected directly to the lake.

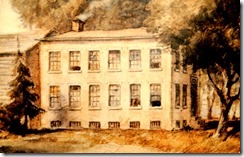

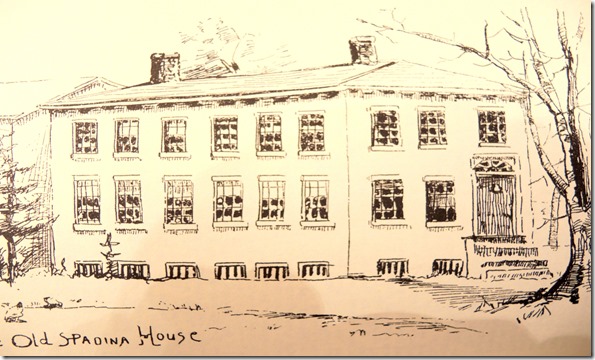

In 1818, Baldwin finally constructed his dream home. He named it Spadina, an Anglicised version of the Ojibwa word “ishpadinaa,” meaning a “hill or a sudden rise of land.” Henry Scadding wrote rather condescendingly in “Toronto of Old,” published in 1873, that the word “ishpadinaa” had been “tastefully modified.” On the left is a watercolour of it, painted in 1912 by Owen Staples, based on a sketch of 1888. The watercolour is in the collection of the Toronto Public Library. A description of the house is contained in a letter written by William Baldwin in 1819. “I have a very commodious house in the Country . . . The house consists of two large parlours, hall and staircase on the first floor—four bedrooms and a small library on the 2nd — three Excellent bed rooms in the attic storey or garret — with several closets on every storey, a kitchen, dairy and root cellar, wine cellar, and man’s bedroom underground.” It was indeed a luxurious residence for a “country home,” as Baldwin owned another house in the town.

To improve the view from his residence,” Baldwin cleared 300 feet of wild growth to the south of it, between the house and the edge of the escarpment. When completed, it provided a panoramic view of the land below the heights, which included the wide carriageway that became Spadina Avenue. In the distance, the town was visible, nestled beside the waters of Lake Ontario.

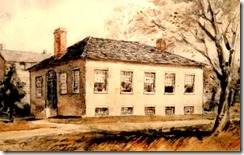

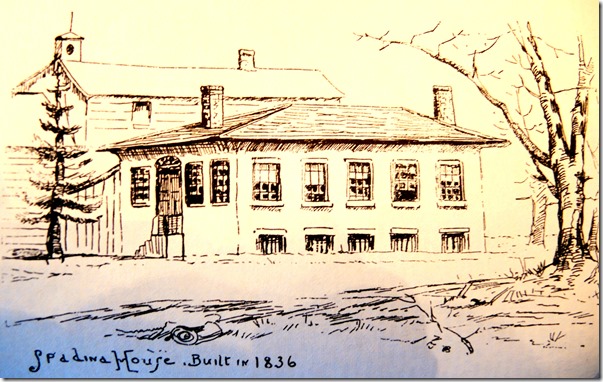

Unfortunately, Spadina House burnt in 1835. Baldwin was now 60 years old, and rather than live on the remote property atop the hill, he moved into his mansion on the northeast corner of Bay and Front Streets. However, he erected another country home above the hill in 1836, but the one-story dwelling was more modest in size compared to the original Spadina House. The watercolour on the left depicts the second Spadina House, painted by F. W. Poole in 1912, from a sketch drawn in 1888.

William Baldwin died in 1844 and the property passed to his son Robert Baldwin. He began sub-dividing the estate, selling parcels of land to prospective buyers. By 1866, only 80 acres remained and at an auction, they were purchased by the founder of The Dominion Bank and president of the Consumers’ Gas Company—James Austin.

James Austin was born March 6, 1813. His family immigrated to Upper Canada (Ontario), arriving in York (Toronto) in October 1829. For two months, the Austins sought to establish themselves on a farm close to York (Toronto). Unsuccessful, they settled in Trafalgar Township in the Oakville area. When James was sixteen, he was apprenticed to William Lyon Mackenzie in his printing shop. Austin spent four and a half years with Mackenzie before establishing his own printing business. After the rebellion of 1837, he relocated to the United States, since it was too risky to remain in Toronto for anyone with connections to Mackenzie, “the rebel.” In 1843, Austin determined that it was safe to return to Canada West (Ontario).

Austin had earned sufficient funds while in the United States to open in Toronto a wholesale and retail grocery business in partnership with another Irishman, Patrick Foy. Austin eventually amassed further funds by investing in banking and natural gas. In 1866, in an auction, with a successful bid of £3,550, he purchased Spadina House, built by William Warren Baldwin. He demolished the house and erected a grand residence on the site, which he named Spadina. No architect was listed. It was the third house constructed on the site that possessed the name “Spadina.”

Austin’s home had two-storeys, although a third floor was added sometime between 1905 and 1915. In 1866, the entrance hall, with its intricately carved woodwork and elaborate crown mouldings, was built to impress visitors. Austin was an avid hunter and placed two stuffed wolves on either side of the interior of the doorway. Stuffed animals of various species were very popular among the wealthy at this time. Upon entering the entrance hall, guests had an unobstructed view of the magnificent grand staircase. This added to the sense of awe that Austin was desirous of creating.

The drawing room (parlour), the most impressive room in the house, was on the right-hand (south) side of the entrance hall. For the comfort of guests, due the room’s size, it possessed two white marble fireplaces, one at each end of the room. On the south side of the drawing room was the palm room, a sunny greenhouse-like area containing many potted flowering plants, as well as palms. Large doors on the south side of the palm room opened onto the outdoor terrace that overlooked the lawns and the city in the distance, to the south.

The dining room was also on the first floor, the room’s windows facing east to catch the morning light. It was relocated in the years ahead, and the former dining room became the library. The spacious kitchen was close to the dining room. It was bright and cheerful, unlike most kitchens in wealthy homes of the period, which were in the basement. To supplement the kitchen there was a pantry, scullery, storage space, and a large built-in icebox.

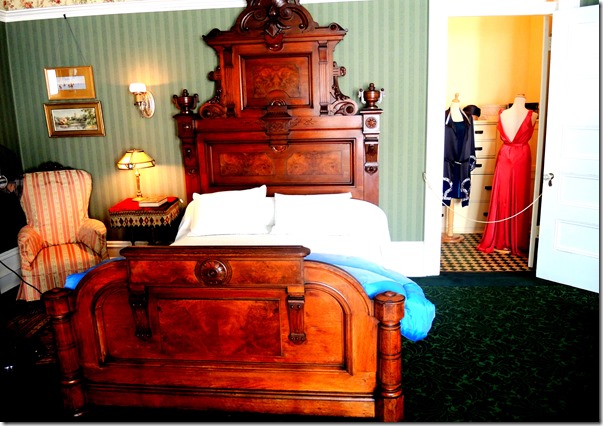

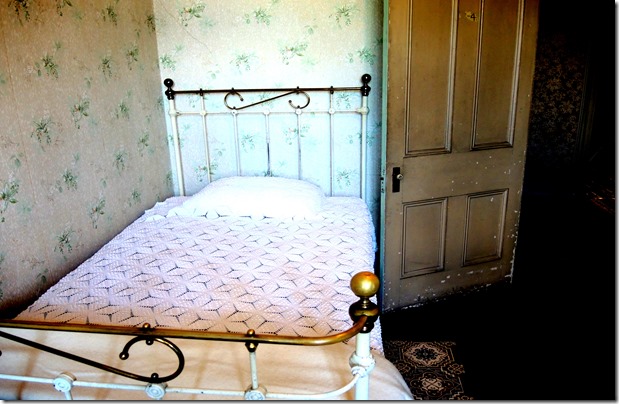

The grand curved staircase in the entrance hall led to the second floor. There was an intimate sitting room at the top of the stairs (the Blue Room). The bedrooms on the second storey were spacious and well furnished.

The home greatly impressed the citizens of Toronto. Henry Scadding in his book “Toronto of Old,” published in 1873, wrote: “. . . before us to the north, on the ridge which bounds the view in the distance, we discern a large white object. This is Spadina House, from which the avenue into which Brocks Street passes takes its name.”

In the years after Spadina was built, other wealthy families purchased property from James Austin to erect their own mansions. By 1889, only 40 acres remained of the land that had comprised the original Austin estate. In 1892, James Austin passed the title of Spadina and the land surrounding it to his son, Albert William Austin. James Austin passed away in 1897.

Albert and Mary continued to expand Spadina. An extension was added on the north side that contained a new dining room, its windows facing west. As mentioned, the former dining room became a library, but in reality it was employed as an extension of the drawing room. During this period, Albert and Mary added two more bedrooms, improved servants’ quarters, and constructed a circular driveway and new kitchen. One of the most impressive additions was a magnificent billiard room, designed by the popular 19th-century architect W.C. Vaux Chadwick. The room also possessed colourful murals by interior decorator Gustav Hahn, who pioneered Art Nouveau in Canada.

A beautiful and visually prominent canopy of handcrafted wrought iron and glass was erected over the main door. Referred to as a “porte-cochère,” it was designed by Carrere and Hastings. It protected guests and family members that arrived by vehicle from the weather. It is likely that at the same time the enclosed porch was added, and the main doorway relocated so that it faced west, rather than south.

Albert constructed a two-storey stucco garage in 1909, which contained a chauffeur’s residence on the second floor. In 1913 a greenhouse was added to the property, its entrance possessing a Gothic-style doorway. There were now 13 bedrooms, most of them for guests. The servants at Spadina were housed on the third floor, each having their own room, though they shared a toilet, bath and sitting room. By 1913, the house was complete and appeared much the same as it appears today.

Because the family was among the most prominent in the city, an invitation to dine at Spadina was highly coveted. During formal dinners in the 1920s, Mrs. Mary Austin (wife of Albert) always sat at the head of the table, nearest to the kitchen, permitting her to inspect the food when it appeared. A small foot-pedal under the table allowed her to summons the staff surreptitiously to remove empty dishes and to signal when the next course was to be served. Thus, she controlled the pacing of the meal.

After the dining ended, guests retired to the drawing room (parlour) on the opposite side of the entrance hall. The drawing room was where they discussed the news of the day, gossiped, or were entertained. When the family was alone, in the evenings, the smaller parlour (sitting room) on the second floor was likely employed for intimate family moments.

Eventually, Albert sold all of the land of the estate except for about 10 acres. A large portion was purchased by the City of Toronto for the construction of the St. Clair Reservoir. However, Spadina House remained in the possession of the Austin family until 1982. In this year, the house, most of its contents, and the remaining land were acquired through donation and purchase by the Ontario Heritage Foundation and the City of Toronto. This was arranged by Spadina’s last resident, Anna Kathleen Thompson, the daughter of Albert and Mary Austin. At the time, she was over 90 years of age.

The home and grounds were restored by the City of Toronto and were opened to the public as a museum in 1984.

Sources for this article :www.biographi.ca/en/bio/austin_james_12E.html,

https://theculturetrip.com › North America › Canada,

https://www.thestar.com › Life › Fashion & Style

Sketch of Baldwin’s Spadina House, built in 1818. The drawing first appeared in the Evening Telegram series, “Landmarks of Toronto” in December 1888.

Sketch of the second Spadina House built in 1836. The drawing first appeared in the Evening Telegram series, “Landmarks of Toronto” in December 1888.

Spadina House in 1885, a view of the north and west facades. The porch on the west facade no longer exists and the third storey had not yet been built. Photo from the Spadina Collection.

North and west facades of Spadina House in 1898. Photo from the Spadina Collection.

View of the south facade in 1905, before the third storey was added. Photo from the Spadina Collection.

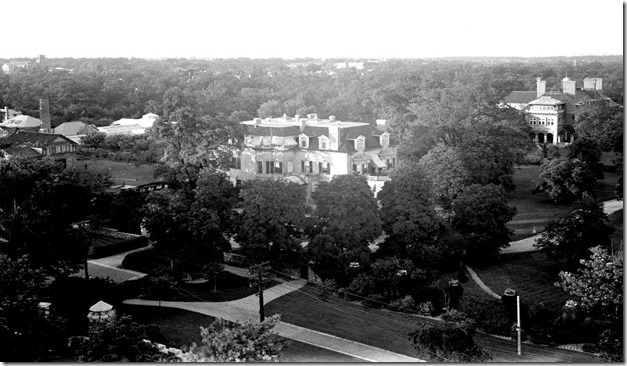

View of Spadina House in 1915 from a tower of Casa Loma. By this year, the third storey of the house has been added. The camera is pointed to the northeast. Toronto Archives, F 1244, item 4135.

View gazing to the northeast at the three-storey Spadina House in 1985. The palm room and veranda above it on the second storey face south. Toronto Public Library, tspa 0113049f

The drawing room (living room or parlour) of Spadina House in 1988, one of the white marble fireplaces visible at the far end of the room. The chandeliers of cut-glass, referred to as gasoliers (gas-run chandeliers), are still in working order. They hang from the 14-foot ceiling. The doorway on the far-left leads to the library, which was originally (in 1866) the dining room. Public Library tspa 0113051f.

View of the drawing room in 2018, the large window facing south. The doorway on the extreme right-hand side leads to the palm room.

(Left photo) Ornate crown moulding above the green wallpaper in the drawing room, and in the right-hand photo, one of the gasoliers (chandeliers) with a fancy plaster medallion above it.

The palm room on the south side of the house. It is accessed from the drawing room and on its south side are doors leading to the outdoor terrace.

Grand staircase in the entrance hall that gives access to the second floor. The doorway at the foot of the stairs leads to an enclosed sunlit porch that was added to the house c. 1905.

One of the stuffed wolves in the enclosed porch. Behind it is where the south-facing doorway was located in 1866, prior to the porch being built.

View of the grand staircase from the entrance hall.

The dining room in Spadina House, in an addition built by Albert and Mary. A large gas fireplace is at the far (north) end of the room. A thick red curtain covers the doorway where the servants entered to serve meals.

View of the grand staircase from the second floor.

Second-storey sitting room (blue room) at the top of the grand staircase.

The bedroom of Mrs. Austin on the second floor level. Originally, Albert and Mary shared the same bedroom, but later, Albert slept in a separate bedroom.

The kitchen on the ground floor, located beside the family’s formal dining room.

The kitchen cupboard containing products employed in preparing the meals for the family.

(left) The wood stove in the kitchen that has gas burners atop it, and (right) a gas stove.

A servants bedroom on the third floor of Spadina House. The Austins had a household staff of five: a gardener, a chauffeur, two maids and a cook.

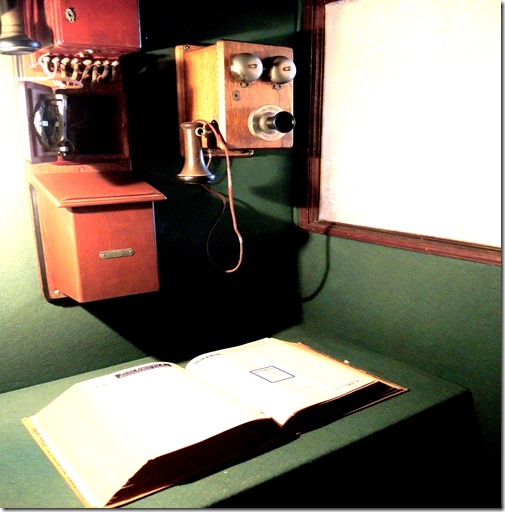

The small telephone room was in a former cupboard in the first-floor hallway. It was insulated with felt to muffle the voices of people who felt that they must shout into the device to make themselves heard. Many people today do the same thing when talking in public on their IPhones. On the table is a Toronto phone book from the 1920s.

The Austin’s bathroom, which has a small gas burner to warm the shaving cream of the Austin men.

Small gas burner in the bathroom to warm men’s shaving cream.

The billiard room on the ground floor, with a cork floor surrounding it to give the players better traction when playing.

The billiard room in 1988, the cork floor around the table evident. Photo Toronto Public Library, tspa 0113050.

The billiard room, designed by the popular 19th-century architect W.C. Vaux Chadwick, the influence of the Art Nouveau movement evident. The murals on the upper portion of the walls depict birds, trees and a colourful sky. They were painted by interior decorator Gustav Hahn, who pioneered Art Nouveau in Canada.

The murals and stuffed animals in the billiard room.

Greenhouse with its Gothic-style entranceway, built in 1913.

(Left photo) The garage with chauffer’s quarters on the second floor, built in 1909. (right-hand photo) An outbuilding that was first a barn, then a coach house and finally, in 1909, renovated to create a cottage for the gardener.

View looking west from under the wrought iron and glass “porte-cochère” (canopy) designed by Carrere and Hastings. It protected guests and family members that arrived by vehicles from the weather.

The east facade (rear) of Spadina House in 2014.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

Books by the Blog’s Author

“ Lost Toronto”—employing detailed archival photographs, this recaptures the city’s lost theatres, sporting venues, bars, restaurants and shops. This richly illustrated book brings some of Toronto’s most remarkable buildings and much-loved venues back to life. From the loss of John Strachan’s Bishop’s Palace in 1890 to the scrapping of the S. S. Cayuga in 1960 and the closure of the HMV Superstore in 2017, these pages cover more than 150 years of the city’s built heritage to reveal a Toronto that once was.

“Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses. To place an order for this book, published by History Press:

Book also available in most book stores such as Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox and AGO Book Shop. It can also be ordered by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

“Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again” explores 81 theatres. It contains over 125 archival photographs, with interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating histories. Note: an article on this book was published in Toronto Life Magazine, October 2016 issue.

For a link to the article published by |Toronto Life Magazine: torontolife.com/…/photos-old-cinemas-doug–taylor–toronto-local-movie-theatres-of-y…

The book is available at local book stores throughout Toronto or for a link to order this book: https://www.dundurn.com/books/Torontos-Local-Movie-Theatres-Yesteryear

“Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. It contains archival and modern photos that allow readers to compare scenes and discover how they have changed over the decades. Note: a review of this book was published in Spacing Magazine, October 2016. For a link to this review:

spacing.ca/toronto/2016/09/02/reading-list-toronto-then-and-now/

For further information on ordering this book, follow the link to Amazon.com here or contact the publisher directly by the link below:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21

![1985 tspa_0113049f[2] 1985 tspa_0113049f[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/1985-tspa_0113049f2_thumb.jpg)

![1988. drawing room tspa_0113051f[1] 1988. drawing room tspa_0113051f[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/1988-drawing-room-tspa_0113051f1_thumb.jpg)

![1988. billiard room tspa_0113050f[1] 1988. billiard room tspa_0113050f[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/1988-billiard-room-tspa_0113050f1_thumb.jpg)

![DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[2] DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/dscn2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_2_thumb.jpg)