Tollkeeper’s Cottage at 750 Davenport Road, in early-June 2014.

The small, unpretentious cottage in Tollkeeper’s Park, on the northwest corner of Bathurst Street and Davenport Road, is not well known by most Torontonians. This might appear strange considering it overlooks one of the busiest intersections in the city. Hundreds of cars pass it daily, but few drivers ever give it a glance. Unfortunately, I must include myself among those who, until recently, took little notice of it.

Perhaps the reason for its relative obscurity is that except for Scadding Cabin on the CNE grounds, it is the most modest in size of all Toronto’s heritage properties. Casa Loma, St. Lawrence Hall, Spadina House, Campbell House, George Brown House, and Colborne Lodge reflect the lives of those who possessed considerably more wealth. Even Mackenzie House, which is quite modest, is rather grand compared to the tollkeeper’s cottager.

Yet the latter is important in our history as it is one of the oldest structures in the city and showcases the lifestyle of the poorest citizens of its era. Even today, such people are often overlooked. Proof of this is the fact that except for the dedicated efforts of a group of local historians, the Community History Project (CHP), the cottage would have been demolished. The CHP was founded in 1983 and four years later was incorporated as a not-for-profit corporation.

The tollkeeper’s cottage hearkens back to a time when Toronto was a small colonial town named York, nestled beside the eastern end of the harbour. At that time, the land around Bathurst Street (then known as Cruikshank’s Lane) and Davenport Road remained open fields and farmland, remote from the town to the southeast. However, even in that era, Davenport Road was an important thoroughfare, one of the oldest in the province of Upper Canada (Ontario). It was located at the base of an escarpment, created when the great sheets of glacial ice retreated. For centuries, it had been a path traversed by Native Peoples. In the final years of the 18th century, it became a narrow dirt road employed by early-day settlers. Interestingly, it appears on a map drawn in 1796 by Elizabeth Simcoe.

In the early-1800’s, constructing roads to facilitate travel was beyond the financial capabilities of the government of Upper Canada (Ontario). The hinterland of the town of York was heavily forested, requiring considerable labour and expense to clear if roads were to be built. As a result, in 1835, the government auctioned off the rights to construct and maintain sections of road. In return, the investors were allowed to collect tolls from those who travelled them.

Davenport Road was viewed as one of the better investments, resulting in five tollgates being built on the plank roadway. Tollgates required a tollkeeper, and as travellers used the roads constantly throughout the day and during the hours of darkness, it was essential that tollkeepers reside beside the tollgates. As a result, small cottages were built for the tollkeepers and their families. They were often constructed to allow the occupants to lean out a small window to collect the tolls. Women were never officially hired for the position, although they were often the ones who actually collected the tolls. This was because tollkeeper’s wages were a pittance, which resulted in their husbands being absent from the tollgates as they laboured at a second job or worked a small farm.

The cottage for Tollgate #3 was situated on the southeast corner of Bathurst and Davenport, where Starkmans Health Care Depot is today. This was confirmed by an 1875 painting by Arthur Cox. It appears that the cottage dates from c. 1835, as it has building features from between the years 1820s and 1840s. It is also believed that because it contains re-used materials from other locations, it may have been constructed on another site and moved to Bathurst and Davenport Road.

The Tollkeeper’s Cottage has three-rooms and an attic with a low ceiling and no windows. It was primarily employed for storage. The cottage is constructed of vertical planks of white pine, 2 inches thick and 30 inches wide. Very few structures of this type have survived into the modern era. Clapboard siding was nailed horizontally over the vertical planks. The cottage was approximately 20’ by 30’, containing a front and a back entrance. The floors were of hand-planed pine and the interior walls of plaster. In the kitchen there was a fireplace, the cottage’s only source of heat. It was later replaced by an iron stove.

During the 1860s, the tollkeeper’s at Tollgate #3 was John Bullmin. He and his wife Elizabeth slept in one bedroom, and their four daughters shared the second bedroom, sleeping two to a bed. Their three sons slept on the floor in the main room, which perhaps was not so bad as it was heated by the wood stove. In the warmer months, the boys likely slept in the shed, which was attached to the west side of the cottage.

In a decade lacking electricity and modern appliances, there were many more back-breaking household chores than today. Among them was to trudge to Taddle Creek, in Wychwood Park, to retrieve water for the family’s needs. Other tasks would include untying the ropes that held the straw mattresses in place, carrying the mattresses outside and beating them to eliminate bedbugs. Food preparation and preserving fruits for the long winters were labour-intensive chores, as was gathering wood for the fireplace and later, the iron stove.

As mentioned, tollkeepers usually had a second source of income. John Bullmin farmed 6.5 hectares of land, and the 1861 census reveals that his wife churned 50 pounds of butter that year with the milk from the family cow. It was a harsh life. Adding to the difficulties was the fact that, as one might suspect, tollkeepers were not popular and were often abused by the general public.

Either John or Elizabeth had to be available seven days a week, year round, in all types of weather, to collect fees from those using Cruikshank’s Lane (Bathurst Street). Each time a traveller appeared, it was necessary to open the tollgate manually. Records from 1851 show that the fee for a wagon drawn by two horses was six pence, a one-horse wagon three pence, and a single horse two pence. Those travelling on foot accompanied by up to 20 cattle or sheep, paid a penny. The clergy and the military were not charged and there were no fees on Sundays to encourage people to attend church. It is not known how many years John Bullmin remained as the tollkeeper. His tombstone in the Toronto Necropolis cemetery, near Riverdale Farm, states that he died in 1867, although his wife lived until 1912.

In 1895, the toll system was abolished by the government and Davenport Road became toll free. As the small cottage for Tollgate #3 was no longer required, it was sold. The buyer relocated it to a lot on Howland Street, two blocks east of Bathurst Street, where it became a family residence. Eventually, a larger structure was erected in front of the cottage to enlarge the living space. Thus, the cottage was no longer visible from the street.

It was basically forgotten until 1996, when a developer was planning to demolish the cottage and the home in front of it to clear the site for a condominium. A neighbour, who was aware of the history of the cottage, alerted the group known as the Community History Project (CHP). The CHP authenticated the information, proving that hidden under the layers of siding on the walls and the asphalt on the roof was indeed the historic tollkeeper’s cottage. It is thought to be the only dwelling that remains in Canada today that was lived in by those who collected tolls from early-day roads.

An agreement was negotiated by CHP whereby the condo developer would sell the cottage to them for $1, with the stipulation that it be relocated as soon as possible. The group raised funds and succeeded in arranging an agreement with the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) that until a permanent site was found, it could be relocated to the Wychwood Streetcar Barns. In June 1996, the move occurred. It remained at the Wychwood yards for the next six years. During this period, the restoration of the cottage began.

It was a monumental task, as there were several layers of material covering the original exterior clapboard siding, as well as on the interior walls of the rooms. On the roof, there were seven layers of asphalt shingles. All the extraneous materials were carefully removed, and despite the structure’s poor condition, it was revealed that 80% of the original building was intact. The task now was to restore it to its original state.

To finance the ongoing work, over 500 donors provided funding and finally, a grant was given by the Ontario Trillium Fund. However, a permanent site for the cottage was still required. In 2002, Toronto City Council voted to give it a permanent home in Davenport Square Park, which was to be renamed Tollkeeper’s Park. This action formally recognized the importance of the cottage in the history of the city.

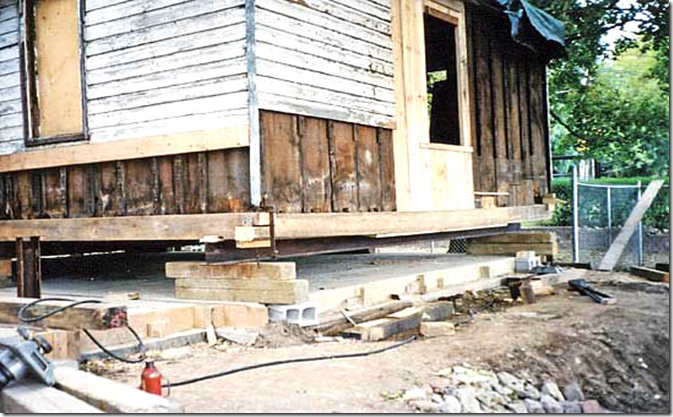

After it was relocated to its present-day site, further restoration commenced. The horizontal beams at the base of the structure that supported the vertical planks had deteriorated to the extent that they needed to be replaced. Since most of the original clapboard had survived, it was possible to replace the missing parts with accuracy. In late-November, as the year 2002 drew to a close, volunteers laboured in freezing weather to protect the historic building during its first winter in its new location.

After the work was completed, the CHP decided to furnish it to reflect the 1860s, when John Bullmin and his family resided in the cottage. In 2003, the City of Toronto officially declared the Tollkeeper’s Cottage a heritage site. It was opened to the public on July 1, 2003. To enhance the experience for modern-day visitors, an addition was erected at the rear (west side) of the cottage, providing space for a museum and interpretive centre.

Though the cottage is not situated on its original location, it is very close. The original site is now under the asphalt at the intersection of Davenport Road and Bathurst Street. This occurred when the roadways were widened to meet the needs of the modern era.

Sources:

https://www.thestar.com › Your Toronto › Once Upon a City

streeter.ca/midtown/news/no-toll-charge-at-midtown-museum/

www.tollkeeperscottage.ca/html/Background.htm

https://www.geocaching.com/seek/cache_details.aspx?guid=af553a91-c921-411c…

http://torontosavvy.me/tag/tollkeepers-cottage-toronto/

The painting is by Arthur Cox and was completed in 1875. The couple in the foreground is seated on the top of the Davenport Road hill, the man pointing southeast. Below them is the intersection of Bathurst Street and Davenport Road, where the tollkeeper’s cottage is on the southeast corner. The City of Toronto had not yet expanded this far north and the land below the hill was mostly farmland. On the left can be seen a steep pathway that ascends the hill. The copyright of the painting belongs to the Community History Project.

Removing the cottage from its site on the corner of Howland Avenue and Davenport Road in June 1996. Photo from “Toronto Savvy.”

Transporting the cottage westbound along Davenport Road in June 1996. Photo from “Toronto Savvy.”

Volunteers remove extraneous layers of materials from the roof and walls of the Tollkeeper’s Cottage in May 2001. This was performed while the cottage was temporarily located at the Wychwood Streetcar Barns. Portions of the original clapboard have been exposed. Photo from a display at the Tollkeeper’s Cottage.

The cottage on its site in Tollkeeper’s Park. In this photo, the vertical pine planks that support the roof are visible, as well as the clapboard siding that covers them. Photo from “Toronto Savvy.”

The cottage after it was moved in 2002 from the Wychwood Streetcar Barns and placed on its permanent home at Tollkeeper’s Park. The foundations that will support the cottage are visible. Photo from “Toronto Savvy.”

The official opening of the cottage to the general public on July 1, 2003. Photo from “Toronto Savvy.”

The cottage after it was restored. Photo taken in 2014.

The main room of the cottage, where cooking and meals occurred, was the only room that was heated. View faces the front (east) door. The stove is placed where the fireplace had once been. Photo taken 2018.

Table in the main room where the family gathered for meals. I have no idea why a rooster is on the table.

Bedroom furnished as it might have appeared when Mr. and Mrs. Bulmin slept in it.

The room where the four Bulmin daughters slept.

The bedroom of the girls, looking toward the main room on the south side of the cottage. In the ceiling the trap door is visible that gave access to the attic.

The cottage with its front porch facing east and at the rear, the museum and interpretive centre.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

Books by the Blog’s Author

“ Lost Toronto”—employing detailed archival photographs, this recaptures the city’s lost theatres, sporting venues, bars, restaurants and shops. This richly illustrated book brings some of Toronto’s most remarkable buildings and much-loved venues back to life. From the loss of John Strachan’s Bishop’s Palace in 1890 to the scrapping of the S. S. Cayuga in 1960 and the closure of the HMV Superstore in 2017, these pages cover more than 150 years of the city’s built heritage to reveal a Toronto that once was.

“Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses. To place an order for this book, published by History Press:

Book also available in most book stores such as Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox and AGO Book Shop. (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

“Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again” explores 81 theatres. It contains over 125 archival photographs, with interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating histories. Note: an article on this book was published in Toronto Life Magazine, October 2016 issue.

For a link to the article published by |Toronto Life Magazine: torontolife.com/…/photos-old-cinemas-doug–taylor–toronto-local-movie-theatres-of-y…

The book is available at local book stores throughout Toronto or for a link to order this book: https://www.dundurn.com/books/Torontos-Local-Movie-Theatres-Yesteryear

“Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. It contains archival and modern photos that allow readers to compare scenes and discover how they have changed over the decades. Note: a review of this book was published in Spacing Magazine, October 2016. For a link to this review:

spacing.ca/toronto/2016/09/02/reading-list-toronto-then-and-now/

For further information on ordering this book, follow the link to Amazon.com here or contact the publisher directly by the link below:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21

![1875, Art Cox reproduction -0.0.1200.806-0.0[1] 1875, Art Cox reproduction -0.0.1200.806-0.0[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/1875-art-cox-reproduction-0-0-1200-806-0-01_thumb.jpg)

![albert-fulton-tollkeeper-cottage-in-Tor. Archives transit-fonds-128-4-july-9-pm1[1] albert-fulton-tollkeeper-cottage-in-Tor. Archives transit-fonds-128-4-july-9-pm1[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/albert-fulton-tollkeeper-cottage-in-tor-archives-transit-fonds-128-4-july-9-pm11_thumb.jpg)

![Tor. Savy tollkeeper2[1] Tor. Savy tollkeeper2[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/tor-savy-tollkeeper21_thumb.jpg)

![5-layers-550cap[1] 5-layers-550cap[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/5-layers-550cap1_thumb.jpg)

![c07513f0-2fa4-4d2f-b0e6-7e198649aa81[1] c07513f0-2fa4-4d2f-b0e6-7e198649aa81[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/c07513f0-2fa4-4d2f-b0e6-7e198649aa811_thumb.jpg)

![opening day July 1, 2003 Tor. Savy tollkeeper8[1] opening day July 1, 2003 Tor. Savy tollkeeper8[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/opening-day-july-1-2003-tor-savy-tollkeeper81_thumb1.jpg)

![DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[2] DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/dscn2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_2_thumb.jpg)

![image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1] image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb1_thumb.png)