Toronto’s New City Hall

Many cities throughout the world have landmark structures that are easily recognized, even when there are no captions or context that identify their location. A few prime examples are the Eiffel Tower, United Nations Building, Golden Gate Bridge, Coliseum, Taj Mahal, and Buckingham Palace. If photos of these buildings are displayed, there is no need to identify the city where they appear as they have been well known for decades and in some instances, for centuries.

Toronto possesses two such structures—the CN Tower and the New City Hall. When I was travelling across Europe and Asia in the late-1970s, in the windows of travel agencies, I sometimes saw photos of the New City Hall and the CN Tower. The images were being employed to promote Toronto as a tourist destination. Most people I talked to readily knew where these landmarks were located.

Toronto was not always as well known internationally as it is today. In the 1930s, the city remained a quiet and loyal part of the old British Empire. During the Second World War its economy expanded as it focussed on contributing to the war effort. After peace was declared in 1945, growth was stimulated exponentially by the pent up demand for housing, commercial buildings and entertainment. The post-war years were also when immigration increased immensely as thousands of people chose Toronto as their new home. The city’s growth continued unabated throughout the 1950s. At the end of the decade, development was further intensified by the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959. Ships were now able to bi-pass Montreal, which was at that time was Canada’s largest city. Thus, the 1960s became a period of extremely robust construction.

Unfortunately, because of the city’s rapid expansion during this decade, many of the city’s heritage buildings were demolished. Many low-rise structures in the downtown were destroyed and replaced with towering skyscrapers. It was as if City Council had embraced the motto: “out with the old, in with the new.” Most Torontonians embraced this viewpoint, feeling it was necessary if the city were to enter the modern era.

As a result, few objections were raised about the destruction of older buildings, including those that had survived for over a century. Many believed that these structures had little to contribute to the new urban scene. As well, the voices of those concerned about architectural preservation were mostly absent from the scene.

Unfortunately, some developers, aided by politicians, continue to favour this destructive attitude today, though I admit that things are improving.

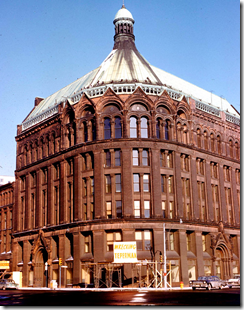

A prime example of the destruction this attitude caused is the demolition of the Board of Trade Building on the northeast corner of Front and Yonge Streets. Built in 1892, it was demolished in 1959 and remained a parking lot until another structure was erected on the site in 1982. The left-hand photo depicts the building constructed in 1982, and the right-hand photo the Board of Trade Building erected in 1892. Readers are invited to compare the two structures and judge accordingly. For more information about the Board of Trade Building: https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/06/11/torontos-board-of-trade-building-demolished/

However, despite the damage created by city planners of the 1960s, it was during this decade that Toronto built a magnificent New City Hall. It began when City Council and Mayor Nathan Philips initiated a world-wide search for an architect. Five hundred and twenty submissions were received from forty-two countries, the winning design by a Finnish architect — Viljo Revell.

Its construction commenced on November 7, 1961, its architecture a dramatic break from the ultra-conservative styles of the past. For over a century, since its incorporation as a city in 1834, Toronto had produced some remarkable buildings, but few that ever created as much praise and condemnation as the New City Hall.

When architectural drawings of it were published in the newspapers, reviews were mixed. One reporter wrote that Revell was to be Mayor Philips’ Christopher Wren, who had designed St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Others declared that the design of the new council chamber resembled an ugly giant oyster, and expressed doubts that any pearls of wisdom would ever be expressed within it.

As construction costs continued to soar, many citizens felt that the entire project was fishy. After all, politicians at City Hall were well known to hook and gut taxpayers by wasting dollars on grand schemes. The unfamiliar futuristic design of the new civic building appeared to be proof of this suspicion. The council chamber in the New City Hall was also compared to a flying saucer. Some expressed the opinion that it might float upward into the skies above due to the political hot air that would be produced inside it by politicians.

However, as the edifice neared completion, people gazed in wonder at the oyster-like city hall chamber, nestled between the two majestic curving towers. Comparisons to fishy endeavours faded from the minds of most citizens, although some still questioned the $25 million building costs. The structure possessed many impressive features, the one that perhaps garnered the most attention being the pillar that supported the council chamber. It was twenty feet in diameter and extended down to the bedrock below. The two towers were not energy efficient by today’s standard, but they were impressive to behold. It was as if Toronto had architecturally finally entered the 20th century.

When the building was officially opened on September 13, 1965 by Governor General Georges Vanier, the weather was cloudy, but nothing dulled the enthusiasm of Torontonians. Fighter planes roared across the sky above the towers and fireworks crackled, sputtered and exploded in the air above it. Mayor Jean Drapeau of Montreal was heard to remark glumly that he doubted that his city would have ever have a building to match it.

Construction site of the New City Hall in 1961, the oval shape of the two towers already evident. The view faces northwest, and in the background are the Toronto Armouries on University Avenue and the Registry Building, located on the west side of the New City Hall (both these buildings have since been demolished). Image is from the Toronto Public Library, a-r4-15

Taken on June 22, 1964, the photo looks northeast from the space that became Nathan Phillips Square. In the foreground is the old Registry Building that is being demolished. To discover the history of this neo-classical structure, follow the link https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/11/torontos-old-registry-office-building/ . The above image is from the Toronto Archives, Fl268, it462.

View of the New City Hall in 1964 as construction nears completion. City of Toronto Archives, F1025, fl 0001, id. 0135.

The New City hall in the late-1960s. Toronto Archives F0124, fl0002, id 0002.

Skaters on the ice in the reflecting pool in Nathan Philips Square, view gazing north. Photo January 15, 2019.

Summer in Nathan Philips Square, view looking north toward the twin towers of the New City Hall, the curved pillars in the foreground extending over the east side of the reflecting pool. Toronto Archives, F 0124, fl 0003, id 0092.

Reflecting pool in Nathan Philips Square, the Canada Life Building in the background and the north facade of the Sheraton Centre Hotel on the upper left-hand corner of the photo.

The 20-foot diameter column that supports the spaceship-like council chamber. The pillar rests on the bedrock below.

City Hall Chambers where city council meets. Photo taken during Doors Open in 2012.

The mayor’s office in the New City Hall, photo taken in 2012.

View from the roof of the Old City Hall, looking west toward the Canada Life Building on University Avenue.

View from the roof of the New City Hall, gazing south over Nathan Philips Square. The large building facing north overlooking the square is the Sheraton Centre Hotel at 123 Queen St. West. Behind it is the CN Tower. On the right-hand (west) side of the square is the eastern part of Osgoode Hall.

View looking east on Queen Street West from the south side of Nathan Phillips Square. The food trucks have been a familiar part of the scene for decades. The tower of the Old City Hall is visible in the background.

View from south side of Nathan Philips Square.

View gazing north from Nathan Philips Square at the New City Hall in the summer of 2012.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

Books by the Author

“ Lost Toronto”—employing detailed archival photographs, this recaptures the city’s lost theatres, sporting venues, bars, restaurants and shops. The richly illustrated book brings some of Toronto’s most remarkable buildings and much-loved venues back to life. From the loss of John Strachan’s Bishop’s Palace in 1890 to the scrapping of the S. S. Cayuga in 1960 and the closure of the HMV Superstore in 2017, these pages cover more than 150 years of the city’s built heritage to reveal a Toronto that once was.

“Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who personally experienced these grand old movie houses. To place an order for this book, published by History Press:

Book also available in most book stores such as Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox and AGO Book Shop. (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2) and may also be purchased on Amazon.com.

“Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again” explores 81 theatres. It contains over 125 archival photographs, with interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating histories. Note: an article on this book was published in Toronto Life Magazine, October 2016 issue.

For a link to the article published by Toronto Life Magazine: torontolife.com/…/photos-old-cinemas-doug–taylor–toronto-local-movie-theatres-of-y…

The book is available at local book stores throughout Toronto or for a link to order this book: https://www.dundurn.com/books/Torontos-Local-Movie-Theatres-Yesteryear

“Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. It contains archival and modern photos that allow readers to compare scenes and discover how they have changed over the decades. Note: a review of this book was published in Spacing Magazine, October 2016. For a link to this review:

spacing.ca/toronto/2016/09/02/reading-list-toronto-then-and-now/

For further information on ordering this book, follow the link to Amazon.com here or contact the publisher directly by the link below:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21

![cityhall- 1960s a-r4-15[1] cityhall- 1960s a-r4-15[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/cityhall-1960s-a-r4-151_thumb.jpg)

![June 22, 1964. f1268_it0462[1] June 22, 1964. f1268_it0462[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/June-22-1964.-f1268_it04621_thumb.jpg)

![f0124_fl0001_id0135[1] f0124_fl0001_id0135[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/f0124_fl0001_id01351_thumb.jpg)

![f0124_fl0002_id0002[1] f0124_fl0002_id0002[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/f0124_fl0002_id00021_thumb.jpg)

![f0124_fl0003_id0092[1] f0124_fl0003_id0092[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/f0124_fl0003_id00921_thumb.jpg)

![DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[1] DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/DSCN2207_thumb9_thumb2_thumb4_thumb_1_thumb.jpg)

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[2] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D8522_thumb.jpg)

![image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1] image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb1_thumb.png)

Without scrolling down in your article, the Board of Trade building was the first lost building to come to mind. Great minds think alike, eh?