The April 2004 edition of “Food and Wine Magazine” declared the St. Lawrence Market to be among the 25 greatest market in the world. I believe this honour is richly deserved. Many people agree when they wander among the food-crammed aisles of the market to view the vast array of cheeses, spices, meats, seafood, produce, and breads. The variety of food seems endless, representing the best of local produce and the finest gourmet treats from around the world. The market scenes resemble an oil painting, rich in colour and texture. It is not only a place to shop, as the market contains numerous cafes and food stalls. One of the most popular is “Buster’s Sea Cove” at the south end of the building. Each Friday, the line-ups for seafood are unbelievable. Another factor that adds to the atmosphere when purchasing items or enjoying a coffee, is the history of this venerable Market.

In1803, Governor Peter Hunter ordered that a farmers’ market be created in the town of York. It was to occupy property south of King Street, east of Church Street, west of Jarvis Street, and north of Front Street. It was built on land reclaimed from and lake and named the St. Lawrence Market, in honour of the Patron Saint of Canada.

At first, the market square was simply a spacious field with a water pump, where local farmers sold their produce and livestock. On Saturdays, farmers arrived from the neighbouring townships, having departed their farms long before daybreak, travelling by horse and cart along the muddy roads that led to the town of York. About the year 1814, they erected a small wooden shelter 35’ by 40’, at the north end of the square, adjacent to King Street. In 1820, the sides of the structure were enclosed.

In 1831, an impressive quadrangular market complex was constructed, stretching from King Street on the north to Front Street on the south.

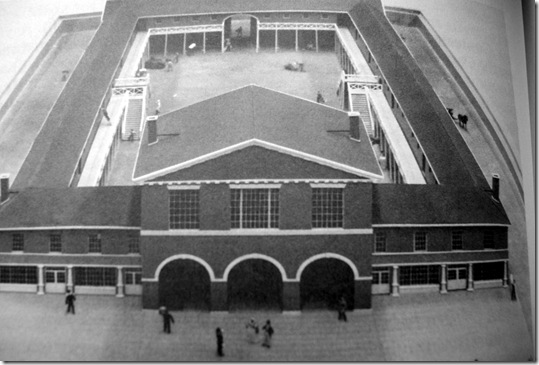

The picture above is a photo of a model of the old market complex of 1831. (City of Toronto Archives)

In the foreground of the above picture is a red-brick market building, with three entrance archways. It fronted on King Street East. The complex included a rectangular central courtyard for farmers’ carts and wagons. Surrounding the courtyard were sheltered spaces with butcher stalls and vegetable stands. The covered section protected vendors and customers from the whims of the weather.

In 1834, the town of York was incorporated as a city and renamed Toronto. Because there was no City Hall, for a decade after its incorporation, city officials met in the red-brick structure on King Street, at the north end of the St. Lawrence Market complex. Thus, the building doubled as both a City Hall and market venue.

In 1844, the market expanded to the south side of Front Street, and in 1845 a permanent City Hall was built on this site. In 1849, fire swept along King Street, destroying the north market. When they rebuilt it in 1851, a grand hall was added – the St. Lawrence Hall. It became the cultural centre for the city, where the citizenry gathered for recitals, concerts, and important speakers.

In 1899, both the north and south market buildings were rebuilt, the construction completed in 1904. The architect was John W. Siddal. The wings on either side of the 1845 City Hall were demolished, as well as its pediment and cupola. The remaining central part of the old structure was incorporated into a much larger building, with sweeping arched walls. It contained plenteous space for food stalls and shops under its massive domed roof. The architectural styles of the north and south buildings complemented each other.

The 1904 south-market building remains to this day, but the north building was rebuilt in 1968. This building is now slated for demolition and a new structure is to be built.

People entering the south building of the St. Lawrence Market today, pass through the archways of the 1845 City Hall. This entranceway and the rooms above it are all that remain of the old City Hall. Today, the council chamber on the third floor contains the Market Gallery, which showcases the art city’s collection, as well as special exhibits.

North facade of the south St. Lawrence Market building of today, with the three stone archways that were a part of the 1845 City Hall. The 1904 building has sweeping walls and a high-domed ceiling that provide ample space for the modern market.

Market stalls and in the background the rear wall of the 1845 City Hall

Colourful shops and stalls along the wide aisles of the market. The great domed-roof floats high over the stalls.

One of the popular meat stalls

Stairs to the basement level

Cafe in the basement, with its colourful mural

View of the south side of the 1904 St. Lawrence Market. The great domed roof is clearly visible.

East side of the 1904 market building, sloping toward where the shoreline of the lake was once locate.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

To view previous blogs about movie houses of Toronto—historic and modern

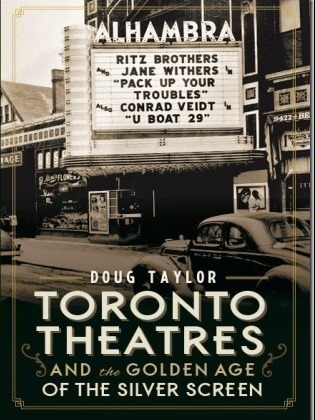

Recent publication entitled “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” by the author of this blog. The publication explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories of the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Store and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791

Theatres Included in the Book:

Chapter One – The Early Years—Nickelodeons and the First Theatres in Toronto

Theatorium (Red Mill) Theatre—Toronto’s First Movie Experience and First Permanent Movie Theatre, Auditorium (Avenue, PIckford), Colonial Theatre (the Bay), the Photodrome, Revue Theatre, Picture Palace (Royal George), Big Nickel (National, Rio), Madison Theatre (Midtown, Capri, Eden, Bloor Cinema, Bloor Street Hot Docs), Theatre Without a Name (Pastime, Prince Edward, Fox)

Chapter Two – The Great Movie Palaces – The End of the Nickelodeons

Loew’s Yonge Street (Elgin/Winter Garden), Shea’s Hippodrome, The Allen (Tivoli), Pantages (Imperial, Imperial Six, Ed Mirvish), Loew’s Uptown

Chapter Three – Smaller Theatres in the pre-1920s and 1920s

Oakwood, Broadway, Carlton on Parliament Street, Victory on Yonge Street (Embassy, Astor, Showcase, Federal, New Yorker, Panasonic), Allan’s Danforth (Century, Titania, Music Hall), Parkdale, Alhambra (Baronet, Eve), St. Clair, Standard (Strand, Victory, Golden Harvest), Palace, Bedford (Park), Hudson (Mount Pleasant), Belsize (Crest, Regent), Runnymede

Chapter Four – Theatres During the 1930s, the Great Depression

Grant ,Hollywood, Oriole (Cinema, International Cinema), Eglinton, Casino, Radio City, Paramount, Scarboro, Paradise (Eve’s Paradise), State (Bloordale), Colony, Bellevue (Lux, Elektra, Lido), Kingsway, Pylon (Royal, Golden Princess), Metro

Chapter Five – Theatres in the 1940s – The Second World War and the Post-War Years

University, Odeon Fairlawn, Vaughan, Odeon Danforth, Glendale, Odeon Hyland, Nortown, Willow, Downtown, Odeon Carlton, Donlands, Biltmore, Odeon Humber, Town Cinema

Chapter Six – The 1950s Theatres

Savoy (Coronet), Westwood

Chapter Seven – Cineplex and Multi-screen Complexes

Cineplex Eaton Centre, Cineplex Odeon Varsity, Scotiabank Cineplex, Dundas Square Cineplex, The Bell Lightbox (TIFF