High Park Mineral Baths on Bloor Street in 1920. Photo from the Toronto Public Library, r-2113

The first time I heard the shrieks and laughter from the swimming pools near High Park was on a June day in the 1940s. My family was attending a Sunday school picnic in the park, and the sky on that Saturday morning was crystal clear, a hint of the afternoon’s heat already evident in the air. I vividly remember the scorching sunshine that day, even after all these years, as it was one of the few times in my life that I received a painful sunburn.

When we arrived at High Park on the Bloor streetcar, I gazed enviously at the hords of bathers crowded around the pool. The explosive splashing of the divers hitting the cool waters of the pools echoed in the morning air. Even though I was unable to swim, I fantasized about crossing over Bloor Street to join the other kids, wishing that I too could scream madly as I jumped from the sky-scraping diving tower. When you are five years of age, you might as well “dream big.”

Alas, despite my imaginary bravado, I was confined to the wading pool inside High Park. Later in the day, I won a book as a prize in the “sack race,” but it did not compensate for being too young to visit the swimming pools. When I was a few years older, I learned that they were the “High Park Mineral Baths,” often referred to as the “Minnies.” Located on the north side of Bloor Street West, they were between Quebec and Glendenan Avenues, across from Toronto’s largest park—High Park. The swimming pools were important during the summer months in Toronto, particularly before the popular pool at Sunnyside Beach opened in 1921.

The site where the mineral baths were located was purchased by George J. Leger in 1889. He was a retired businessman and politician, and when he bought the property, its northern boundary was on Gothic Avenue, its southern boundary on Bloor Street. He built a mansion, carriage house, and stable on the site, its postal address 32 Gothic Avenue. Leger named his mansion “Glandeboye,” after a place in Ireland that he remembered fondly. The view from the house was magnificent as it was on a hill, which on its western side overlooked the deep ravine that led down to Grenadier Pond. It was a wide ravine that was eventually filled in to allow the Bloor streetcar line to extend westward. In the late decades of the 19th century, the area to the north of High Park remained undeveloped, and was considered a rural district to the northwest of the city.

In 1905, George Leger sold the house and land to Dr. William McCormick from Bellevue, Ontario. Dr. McCormick’s wife was also a doctor, and together they renovated the mansion to create the High Park Sanatorium. It officially opened on June 27, 1907, and when full, it accommodated about 20 patient. The facility was associated with Kellogg’s Battle Creek Sanatorium in Michigan. Dr. Harvey Kellogg, the founder of the institution, was the creator of the breakfast cereal, “corn flakes.” Both sanatoriums treated diseases of the nervous system and promoted a healthy life style, stressing daily exercise and proper diet. In 1913, to assist his patients, Dr. McCormick built an outdoor swimming pool on the southern portion of his property, close to Bloor Street, believing that swimming in it would be therapeutic.

One research source states that the water for the swimming pool was likely from Wendigo Creek, which emptied into Grenadier Pond. However, another source states that the water was derived from artesian wells, one of them 80 feet deep and the other 650 feet in depth. Whatever the source, the water was cold and possessed a beneficial mineral content. It was said that the water was heated to 72 degrees Fahrenheit to accommodate the bathers. The pool’s shape was an elongated rectangle, and it was for the exclusive use of the patients of the sanatorium and their families.

In 1914, a year after the mineral baths were opened, the Toronto Civic Railway Company laid a single-track streetcar line along Bloor Street, westward from Dundas Street to Gothic Avenue. The High Park Mineral Baths were now at the terminus of the line, making them easily accessible by public transportation for residents across the city. The pool was enlarged and in 1915 and opened to the public. Difference hours were reserved for men, women, and mixed bathing. During the summer months, the pool was open from 9 am to 9 pm.

By 1917, because of the popularity of the mineral baths, a second pool was built, its dimensions about 50’ by 100’. The old diving tower was replaced by one that had diving boards on different levels and several slides for descending into the water. Because of the increase in the amount of water needed for the pools, the natural sources became insufficient, and the facility commenced using water from the City of Toronto.

During the 1920s, the mineral baths were among the most highly attended swimming facilities in the city. In 1924, they hosted the Olympic Swimming Trials. During the 1940s and 1950s, the mansion on the hill overlooking the pools was the Strathcona Hospital, which served as a private maternity hospital. However, in the 1960s, plans commenced for the Bloor/Danforth subway. To accommodate the subway line, a portion of the land on the southwest side of the mineral baths was needed. As a result, the pools closed in 1962.

I never had an opportunity to swim in the High Park Mineral Baths, but as a boy, I visited Crang’s Swimming Pool, near St. Clair and Oakwood Avenues. Its source of water was a branch of Garrison Creek. I also can recall a swimming pool named “Pelmo Park,” which was on Jane Street near Church Avenue. As a teenager, I also swam in the heated pool beside Sunnyside Beach. Because Toronto’s summers do not linger long on the calendar, summer swimming was a treasured treat of childhood.

In the 21st century, the magnificent mansion at 32 Gothic Avenue was renovated to create a luxury condominium named “Gothic Heritage Estates.” The three-storey building contains 7 spacious residential units.

Sources for this post: torontoist.com—http://losttoronto2—www.highparknature.org—www.visualreferencelibrary.ca—http”//jamesellisarchitect.wordpress. The archival photos were also extremely helpful in determining the history of the mineral baths.

Location of the High Park Mineral Baths.

The High Park Mineral Baths in 1913, when the pool was used exclusively by the patients of the sanatorium and their families. Photo from Toronto Archives, F1244, Item 8157.

The first pool built on the sanatorium site. In the background, landfill is being dumped to fill in the ravine to allow Bloor Street to be extended westward. Toronto Archives, F1231, It. 292.

Bloor Street near High Park in 1914. This photo illustrates how rural the area was to the north of High Park in the early decades of the 20th century. Toronto Archives, F1244, It. 0018.

The minerals baths on August 29, 1915, after the original pool was enlarged. The mansion that George Leger built in 1889, which was sold to Dr. McCormick, can be seen on the hill, in the background. Toronto Archives F1548, s0393, Item 12314.

A view of the swimming pool in 1916. Toronto Public Library, r-2103.

The High Park Mineral Baths in 1916, Toronto Public Library, r-2085.

A view of the pools on July 6, 1917, looking west from the east side. Toronto Archives, Fonds 200, S. 373, Item 489.

View looking north from Bloor Street in 1920. Visible are the swimming pools and the High Park Sanatorium on the hill. Toronto Public Library. r-4647.

Gazing north from Bloor Street West in 1920. The two buildings on the right-hand side of the photo remain in existence today. The Bloor subway was built behind these buildings. Photo from the Toronto Public Library, r-2086.

View of the pools in 1950, looking south from the hill where the sanatorium was once located. Bloor Street and the northern edge of High Park are in the background. Toronto Public Library, r-2104.

High Park Mineral Baths in 1953, Toronto Public Library, r-2117.

Gazing north to the house at 32 Gothic Avenue in 1953. Toronto Public Library, r-3796.

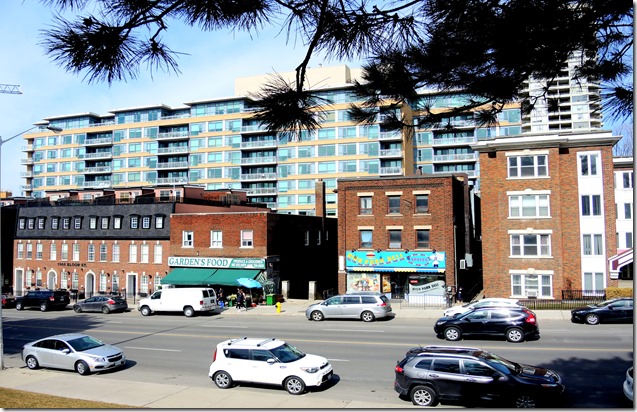

View in 2016 of Bloor Street West, where the High Park Mineral Baths were located.

View of the north side of Bloor Street, opposite High Park in 1920 (left) and in 2016 (right).

The “Gothic Heritage Estates” today, at 32 Gothic Avenue.

Wood trim on the east side of the home of Dr. William McCormick, which was renovated to create a sanatorium.

Verandas on the south and east sides of the McCormick house.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

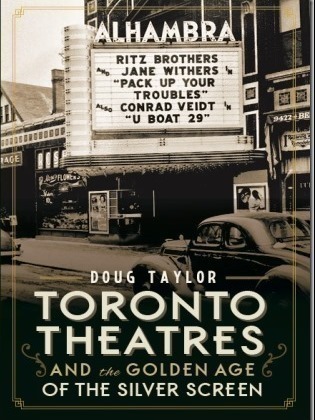

The publication entitled, “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” was written by the author of this blog. It explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Shop, and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

Another book, published by Dundurn Press, containing 80 of Toronto’s former movie theatres will be released in June, 2016. It is entitled, “Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again.” It contains over 125 archival photographs and relates interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating history.

Another publication, “Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. This book will be released on June 1, 2016. For further information follow the link to Amazon.com here or to contact the publisher directly:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21.

![1920--pictures-r-2113[1] 1920--pictures-r-2113[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1920-pictures-r-21131_thumb.jpg)

![data=RfCSdfNZ0LFPrHSm0ublXdzhdrDFhtmHhN1u-gM,7ChuhFYHgamuSd4sfrUDvx5M52G_X5h7KC5c1wLHn7DwtYK2k2mjuQddZacxYho_qm09nShon9qjfLLjZUcLLK8Nb2kuP_O05jRcRLZ[1].png data=RfCSdfNZ0LFPrHSm0ublXdzhdrDFhtmHhN1u-gM,7ChuhFYHgamuSd4sfrUDvx5M52G_X5h7KC5c1wLHn7DwtYK2k2mjuQddZacxYho_qm09nShon9qjfLLjZUcLLK8Nb2kuP_O05jRcRLZ[1].png](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/datarfcsdfnz0lfprhsm0ublxdzhdrdfhtmhhn1u-gm7chuhfyhgamusd4sfrudvx5m52g_x5h7kc5c1wlhn7dwtyk2k2mju1.jpg)

![c. 1911 -high park-mineral-baths-f1244_it8157[1] c. 1911 -high park-mineral-baths-f1244_it8157[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/c-1911-high-park-mineral-baths-f1244_it81571_thumb.jpg)

![1st swimming pool, F1231, It. 292 20140524firstminbaths[1] 1st swimming pool, F1231, It. 292 20140524firstminbaths[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1st-swimming-pool-f1231-it-292-20140524firstminbaths1_thumb.jpg)

![Bloor-west-high-park-1914 F1244, It. 0018 [1] Bloor-west-high-park-1914 F1244, It. 0018 [1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/bloor-west-high-park-1914-f1244-it-0018-1_thumb.jpg)

![Aug. 29, 1915 f1548_s0393_it12314[1] Aug. 29, 1915 f1548_s0393_it12314[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/aug-29-1915-f1548_s0393_it123141_thumb.jpg)

![1915-- pictures-r-2103[1] 1915-- pictures-r-2103[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1915-pictures-r-21031_thumb.jpg)

![1915- pictures-r-2085[1] 1915- pictures-r-2085[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1915-pictures-r-20851_thumb.jpg)

![July 6, 1917. Fonds 200, Series 372, It. 489 20140524minbaths[1] July 6, 1917. Fonds 200, Series 372, It. 489 20140524minbaths[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/july-6-1917-fonds-200-series-372-it-489-20140524minbaths1_thumb.jpg)

![1920, pictures-r-4647[1] 1920, pictures-r-4647[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1920-pictures-r-46471_thumb.jpg)

![1920--pictures-r-2086[1] 1920--pictures-r-2086[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1920-pictures-r-20861_thumb.jpg)

![1950--pictures-r-2104[1] 1950--pictures-r-2104[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1950-pictures-r-21041_thumb.jpg)

![1953-- pictures-r-2117[1] 1953-- pictures-r-2117[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1953-pictures-r-21171_thumb.jpg)

![1953, pictures-r-3796[1] 1953, pictures-r-3796[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/1953-pictures-r-37961_thumb.jpg)

![1920--pictures-r-2086[1] 1920--pictures-r-2086[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/1920-pictures-r-20861_thumb1.jpg)

![image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1] image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb1_thumb.png)

Great post Doug. Just a couple of things that I’ve noticed that you might want to take another look at.

1) A simple mistake: in the third paragraph, you have Clendenan spelled as Glendenan.

2) I’m 99% sure that the photo with the caption starting “Bloor Street opposite High Park, gazing east in 1914”, is actually looking west. That would put the mineral baths off to the right where the tent is seen. The reason I believe the directions are reversed on it is that the image immediately before it has the hydro wires of the opposite side of the road, so the two images have to be looking different directions. The way you can establish which is east and which is west is from the image captioned “Gazing north from Bloor Street West in 1920.” which clearly shows that the hydro lines run along the south side of the street.

Anyway, great post, and I love doing little scraps of heritage detective work like this. Cheers!

Okay, so you’ve updated the post, removing the east-facing image with the sewer (too bad – that was very interesting) and removing the directional information on the west-facing photo. The description on the Toronto archives website confirms to direction. You can put that back and be confident in it! Glendenan is still spelled incorrectly.