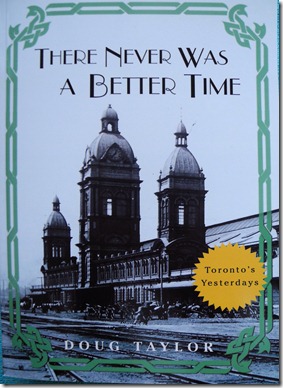

The Dufferin Gate of the CNE in the 1920s. It was built in 1910 and demolished in 1959 to allow for the construction of the Gardiner Expressway.

The “grand old lady of Toronto,” as the Canadian National Exhibition is sometimes referred, has opened for another year. Those of us who knew the Ex in previous decades, lament how much it has changed. Last year as I observed the crowds milling about the midway and flowing into the Food Building, I realized that it remains a place where memories are created. Young people who visit the late-summer fair today are creating their own memories, which in the years ahead, will be as golden for them as our remembrances are for us. My personal memories of the Ex go back as far as 1947, when the Ex reopened after the Second World War. However, I can vividly recall stories of even earlier yesteryears that my dad and grandfather related about attending the great fair.

My father arrived as a young immigrant in Toronto in 1921, and was enthralled with the CNE. Arriving in Canada from a remote coastal village in Newfoundland, prior to the days of confederation, he was overwhelmed by the vast site, enormous ornate exhibition buildings, throngs of people, and variety of foods offered. It was an experience he never forgot, and rarely missed a chance to tell my bother and me about his glorious days at the “wondrous Ex.”

The quotes below are from the novel “There Never Was A Better Time,” a story about my dad, Jack Taylor, and my Uncle Ernie. It tells about their first visit to the CNE in 1921.

In some ways, Jack and Ernie were not to be mere observers at the Ex, but suitors romancing a woman who possessed everything a young man could desire—mystery, beauty, and excitement. Indeed, in this decade, this was the way many people viewed the CNE. It was the highlight of the summer, and perhaps the most singularly important event of the year. By the time the Ex opened, children had grown tired of their rough games in the empty lots and back alleys, and adults were also ready for a more exciting venue. The fair’s arrival made the end of summer seem bearable—perhaps even worthwhile. For schoolchildren, the Ex was a thrilling ritual that would create wistful smiles and dreams that lasted through the first few weeks’ drudgery of the new scholastic year.

As a backwater city of the Empire, Toronto lacked the sophistication of London, Paris, or Rome. Toronto was unable to boast of great cultural institutions or exotic pleasure palaces, but it was still home to the “World’s Largest Annual Exposition.” No citizen questioned this extravagant claim or inquired as to who had compiled the statistics to verify it. All who attended the fair felt capable of assessing it, and there were no doubts in their minds that it was indeed the largest and greatest in the world.

*

The Toronto Star was on the table in front of Jack, and he eagerly read out details about the Ex to Ernie. The fair had opened its gates at eight o’clock that morning. It would cost $600,000 to pay the expenses for the full run of the great exposition. The CNE advertised a “Baby Show” on Labour Day featuring three pairs of identical twins. Other attractions included the “Biggest War Photograph Exhibition in the World.” The Transportation Building was unable to contain the motor exhibition, and thus it had been supplemented with two acres of tents. The Motor Show promised to be a “record-breaker.” Because of the ever-increasing crowds, officials had added three hundred street signs to help people find their way around.

At the Exhibition Art Gallery were numerous treasures, the masterpieces including George Bellows’s The Knock Out, a painting depicting the boxing ring, and A Child and a Dog by John Russell, a sentimental portrayal of youth. The Band Contest would feature seven bands performing classical and modern music. The Business Exhibition highlighted the latest machinery and up-to-date methods for commercial enterprises.

In the old Ontario Government Building, slated to be demolished after the fair closed, were live beavers, moose, fishers, and pheasants, along with an Algonquin Park exhibit. Many a prim and proper elderly woman, after observing the youth among the crowds, remarked that there were perhaps even more animals on the midway. They felt that, since the war, the conduct of the younger generation was not in keeping with the standards of their beloved Queen Mary. They remarked that young people had been more respectful in the days before the war, referring to the Boer War in Africa, which had started in 1899.

The Government Building contained a detailed model of a rural Ontario community, with farms, barns, and fields of pasture and grain. It also depicted a village with houses, a community centre, and shops. All roads, streets, and highways were accurately laid out. The carefully crafted model was certain to amaze everyone.

Although the new livestock building—the Coliseum—remained under construction, there would still be an enormous livestock display. It would include fifteen hundred cattle, nine hundred horses, seven hundred and fifty sheep, five hundred swine, and over sixty-five hundred poultry. Almost every domesticated animal on earth would be exhibited, whether two-legged or four-, surely an accomplishment that rivalled Noah’s Ark.

Jack continued reading aloud other details, but Ernie said nothing in reply, as he was more interested in seeing the events, not reading about them. He knew that if they hurried, they would see the Warriors’ Day Parade. Perhaps they might even catch a glimpse of Lord Byng, who had been sworn in that very month as Governor General. He and Lady Byng were to be present at the CNE’s official opening ceremonies in the afternoon. They were scheduled to review the troops at the Band Stand. With these thoughts in mind, Ernie insisted that his brother eat faster and read less.

*

At the Grandstand at 9:15 pm was a show entitled “Over Here,” a tribute to Canada’s history. Advertisements stated that the show portrayed the founding of Canada, the triumph of civilization, and a nation’s progress. This was no small feat to accomplish within a two-hour presentation, even assuming that civilization had actually triumphed within the borders of the Dominion. A large orchestra had been assembled in front, below the stage, and it provided the music for the extravaganza. There was a community singsong included with each performance, and a giant screen flashed the lyrics to the audience. One of the best-received songs was “Home Sweet Home.” Jack and Ernie longed to attend the show, but lacked the fifty-cent admission. For the remainder of the Saturday evening, they returned to the midway to admire the girls, deciding that this activity was really the best fun of all, and cost nothing.

Shortly after 11 pm, the Grandstand show ended with a dazzling fireworks display that, although it originated south of the stadium, was visible throughout the entire CNE, bursting above the midway and the exhibition grounds. It was Ernie’s and Jack’s first experience of such an event, their previous acquaintance with exhibitions of fire confined to the flames atop the hills on bonfire night in Burin. There was no comparison. The fireworks illuminated the skies in a sparkling array resembling millions of diamonds scattered across the black dome of the universe. The dazzling light reflected off the waters of the lake and illuminated the domes and turrets of the ornate buildings as if it were daytime. The deafening echoes of the explosions reverberated like thunder as they rolled across the grounds.

The downtown towers of modern-day Toronto with their numberless illuminated windows did not exist, and thus the fireworks were the sole man-made lights in the night sky. People gasped and shrieked, their faces reflecting the flashing colours of red, orange, and gold. The evening’s fireworks finally climaxed in a cataclysmic explosion of fire that made it seem as if the end of the world had arrived. In truth, the only thing that had ended was another day at the fair.

At the Grandstand, the words “Good Night” flashed on the giant screen.

City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231, Item 1253

The Grandstand where the 1921 Grandstand show was held. It was destroyed by fire in 1946, and a new grandstand opened for the 1948 season. The new 25,000-seat 1948 grandstand has since been demolished.

![f1231_it1253[1] (3) f1231_it1253[1] (3)](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/f1231_it12531-3_thumb.jpg)