Hotel Hanlan on Hanlan’s Point on the Toronto Islands, c.1908. Toronto Archives Fonds 1244, Item 0176

The Toronto Islands have been viewed as an idyllic recreational escape from the summer’s humid heat on the mainland since the days when Toronto was the small colonial town of York. Ferry service across the bay commenced in the 1833, powered by horses walking on treadmills. The same year, the first small hotel opened on the Islands. Steam-powered boats began crossing the harbour in the 1850s. At the beginning of that decade, the Islands formed a peninsula, until severe storms in 1852 and 1858 washed away the low-lying sandbars that formed an isthmus at the harbour’s eastern end, creating an open channel that became known as the Eastern gap.

The Islands were crown land that was ceded to the City of Toronto after Confederation in 1867. The city leased property on the Islands, but the there was no official plan so the leases and grants were haphazardly parcelled out. However, most people visited the Island on day-trips, the wide sandy beaches on West Point (today’s Hanlan’s Point) particularly attractive to sun bathers. Lieutenant Governor Simcoe referred to this area as Gibraltar Point, but the name now seems to apply only to the southwest part where the historic stone lighthouse is located.

In the early 1870s, City Council studied ways to develop the Islands properly. At the time they were mostly grasslands and trees, many of which were ancient willows, well suited to the low-lying sandy soil. Landfill was employed to create more islands and extend small peninsulas such as West Point.

Because of the increased number of visitors, in the 1860s John Hanlan, an Irishman immigrant and former fisherman, was appointed as constable to patrol the beaches and parklands. In the early 1870s, he built a one-storey frame home on West Point (east of Gibraltar Point) and a wharf beside it. A boathouse adjacent to the wharf accommodated visitors who arrived by boat. During these years, there were few places on the Islands for people wishing to remain overnight. They stayed in tents, boarding houses, and a few small hotels. In 1878, John Hanlan responded to the need and converted his house into a hotel, which by 1880 had expanded to contain 25 rooms.

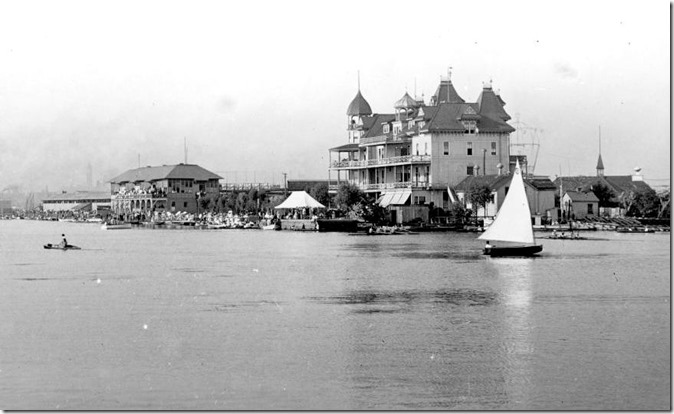

Hanlan’s Hotel and wharf, c. 1880, Toronto Public Library, r-3433

This 1884 map in the collection of the Toronto Archives reveals the location of the Hanlan Hotel, on the northern tip of the peninsula.

This 1889 map depicts Hanlan’s Point and the hotel on the northern tip of the small eastern peninsula. Map by R. L. Polk and Company, Toronto Archives. Landfill joined these two small peninsulas into one land mass and the area to the north of Hanlan’s Hotel was eve eventually filled in, and is where the airport on the Island is located today.

John Hanlan’s son, Edward (Ned) Hanlan, born in 1855, spent his boyhood on the Islands, becoming a skilled oarsman at an early age. While attending George Street Public School on the mainland, he rowed across the harbour each day. When he was 18, he won the championship of Toronto Bay in rowing, a highly popular sport in that day, as it involved extensive gambling. Four years later, he won the American championship, and in 1878, the American title. On November 15, 1880, he won the world championship on the Thames River in England, the first Canadian athlete to receive world recognition. Hanlan won over 300 races during his professional career.

At the pinnacle of his fame, Ned Hanlan took over the management of his father’s hotel. Grateful for the fame Hanlan had brought to the city, Toronto City Council officially changed the name of West Point to Hanlan’s Point, which it retains today. Shortly after, Ned leased 1.2 hectares of land on Hanlan’s Point, near the home where he had spent his boyhood, to extend his father’s hotel business.

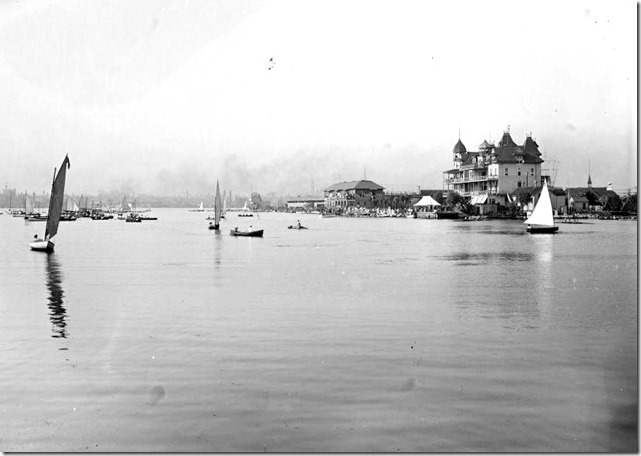

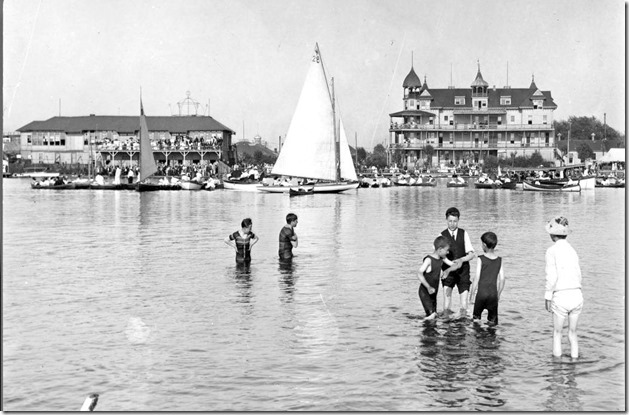

In 1880, he constructed a larger hotel, a three-storey structure in a variation of the Second Empire style, designed by the firm of McCaw and Lennox. It was a frame building, its exterior covered with wide boards cut in a sawmill. Constructed entirely of wood, only the hotel’s foundations contained any masonry. Its overall appearance, with its many wings, ornate trim and pointed cupolas, appeared light and airy. In the eyes of many, it was akin to a summer palace, an ideal place to holiday during the hot, humid Toronto days of July and August. The various sections of the building were topped with pointed turrets containing sloping Mansard roofs. On the east facade there were wide balconies that provided excellent views of Blockhouse Bay, Toronto’s harbour, and the city skyline. The year after it opened, a billiard room and bowling alley were added.

The hotel became the centre of social life on the Islands. Anglican church services were held in its parlour, summer residents picked up their mail there, and the first telephone installed on the Toronto Islands was in the hotel. Four lines of ferries transported overnight guests and day-visitors to the dock in front of the hotel. In 1882, Ned Hanlan leased the hotel to James Mackie, who managed the American Hotel on the mainland. Mackie enlarged the premises by adding a fourth floor and also constructed a summer opera house and carousel.

C. Pelham in his book, “Toronto Past and Present,” written in 1882, stated that at the Hotel Hanlan, “. . . the table d’hote [fixed-price menu] and restaurant are well known to the citizens of Toronto, and the enjoyment of a nice dinner in the cool of the evening, has come to be known as one of Toronto’s luxuries.“

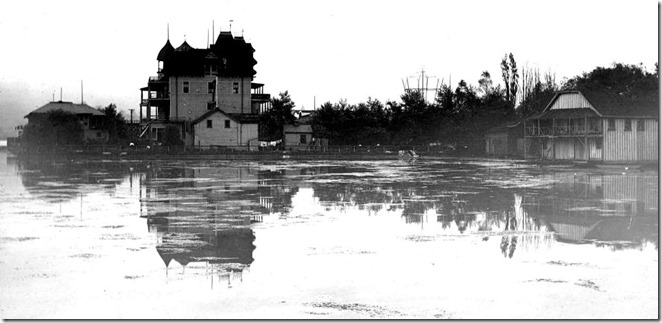

Ned Hanlan died of pneumonia in 1908, the funeral service held in St. Andrew’s Church. He was buried in the Necropolis Cemetery on Winchester Street in Cabbagetown. Sadly, the magnificent hotel was destroyed by a fire that swept Hanlan’s Point on August 10, 1909.

Note: the author is grateful to the book, “Lost Toronto,” by William Dendy, Oxford University Press, 1978, for some of the material contained in this post.

Map of 1903 from the Toronto Archives. It reveals the location of the Hanlan Hotel overlooking Blockhouse Bay, and the amount of landfill employed to create land to build the amusement park at Hanlan’s Point.

John Hanlan’s Boathouse, his hotel evident in the background, c. 1880. Toronto Public Library, r-3424

Hanlan’s Hotel c. 1890. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 0175

Hotel Hanlan between 1885 and 1895. The carousel is evident on the right-hand side of the hotel. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1478, Item 0013

Hanlan’s Hotel in 1907, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 0163.

Hotel Hanlan in 1907, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1233, Item 6029.

Hanlan’s Hotel 1907, Toronto Archives, Fonds 1478, Item 0164.

The hotel in 1909, the year it was destroyed by fire. Toronto Archives, S1171, Item 1724

Hanlan’s Hotel in 1909, Toronto Public Library r- 3441

Postcard of the Hanlan’s Hotel, c. 1909, Toronto Public Library, pcr-2146

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

A link to view previous posts about the movie houses of Toronto—historic and modern.

A link to view posts that explore Toronto’s Heritage Buildings:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2014/01/02/canadas-cultural-scenetorontos-architectural-heritage/

The publication entitled, “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” was written by the author of this blog. It explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Shop, and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

Another book, published by Dundurn Press, containing 80 of Toronto’s old movie theatres will be released in the spring of 2016. It is entitled, “Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again.” It contains over 130 archival photographs.

A second publication, “Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. This book will also be released in the spring of 2016.

![pictures-r-3433[1] pictures-r-3433[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/pictures-r-34331_thumb.jpg)

![1884 Atlas of the city of Toronto and suburbs from special survey and registered plans showing all buildings and lot numbers r-12[1] 1884 Atlas of the city of Toronto and suburbs from special survey and registered plans showing all buildings and lot numbers r-12[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1884-atlas-of-the-city-of-toronto-and-suburbs-from-special-survey-and-registered-plans-showing-a3.jpg)

![1889, R. L. Polk and Comany, Tor. Archives [1] 1889, R. L. Polk and Comany, Tor. Archives [1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1889-r-l-polk-and-comany-tor-archives-1_thumb.jpg)

![1903 Atlas of the City of Toronto and suburbs founded on registered plans and special surveys showing plan numbers, lots & buildings r-101[1] 1903 Atlas of the City of Toronto and suburbs founded on registered plans and special surveys showing plan numbers, lots & buildings r-101[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1903-atlas-of-the-city-of-toronto-and-suburbs-founded-on-registered-plans-and-special-surveys-sh1.jpg)

![boathouse, 1870-- pictures-r-3424[1] boathouse, 1870-- pictures-r-3424[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/boathouse-1870-pictures-r-34241_thumb.jpg)

![btw, 1885 and 1895 f1478_it0013[1] btw, 1885 and 1895 f1478_it0013[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/btw-1885-and-1895-f1478_it00131_thumb.jpg)

![TRL, 1909, pictures-r-3441[1] TRL, 1909, pictures-r-3441[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/trl-1909-pictures-r-34411_thumb.jpg)

![TRL, 1910--pcr-2146[1] TRL, 1910--pcr-2146[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/trl-1910-pcr-21461_thumb.jpg)

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[2] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/cid_e474e4f9-11fc-42c9-aaad-1b66d8522_thumb5.jpg)