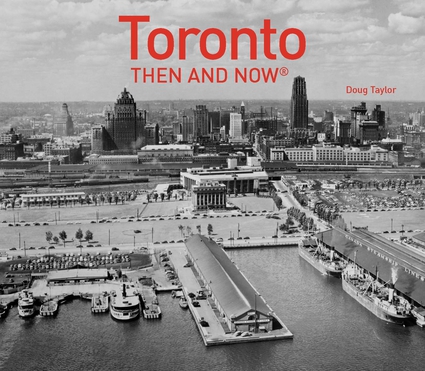

Flooding surrounding a home on Ward’s Island during the spring of 2017. Photo from the Toronto Star, June 3, 2017, accompanying an article by Peter Goffin.

The disastrous flooding of the Toronto Islands during the spring of 2017 has allowed people to realize the importance of the Islands to summer life in the city. Very few urban areas throughout the world possess an idyllic retreat so close to their downtown core. New York has Central Park and Vancouver has Stanley Park, but neither of these resemble the Toronto Islands. Rio de Janeiro has its world-famous beaches, far superior to those on the Islands, but Toronto’s stretches of golden sand appear to satisfy most sun-bathers.

I believe that Toronto’s parkland in the Lake is unique because of its lagoons. They remain virtually unchanged since York’s early-day setters first discovered them in the 1790s. Perhaps this is why a person is able to sense the quieter days of yesteryear when strolling beside their tree-lined banks. It is easy to conjure up images of the picnickers who arrived in the 19th century by flat-bottomed boats powered by horses on treadmills, or envision the ghosts of those who arrived on small vessels propelled by coal-fired steam engines.

The ancient willow trees, stretching their leafy branches to touch the ground, and the wide verdant spaces with the coveted picnic tables remind me of the days of my childhood in the 1940s. My family often arrived on Centre Island on the side-paddled ferry, the Trillium. Because of these memories, today, each summer I journey on at least one pilgrimage to the Islands to reflect upon the days of my youth and enjoy the features added during the previous few decades, especially the gardens.

On these occasions, I purchase a bag of popcorn in Centreville from a small red cart, and suddenly I am an eight-year-old experiencing the wonders of the Islands for the first time. Strolling the down the Avenue of the Islands, across Long Pond on the Venetian-style bridge and wandering south toward the Lake, popcorn in hand, is as close as I am able to get to repeating a childhood ritual. It appears likely that this simple pleasure will be denied me this year, although there remains hope that the Islands will reopen in August.

It seems that I am not alone in lamenting the loss of the Islands this summer (2017). I thoroughly enjoyed Edward Keenan’s article in the Toronto Star on June 3, 2017. For anyone who missed this exceptional piece of writing, it is worth reading it online. Mr. Keenan wrote about the importance of the Islands to the summer season in the city, and shared his present-day thoughts and memories of visiting them. On Tuesday June 6, 2017 he wrote another article in which he asked the unthinkable question—What if the flooding on the Islands is not simply a rare occurrence? but a harbinger of the future, due to climate warming. Mr. Keenan also posed the discomforting question, are we willing to pay to maintain these unique parklands?

The following information is an edited version of a post that I wrote on March 1, 2016, about my childhood memories of the Islands.

Memories of Centre Island during the 1940s

When I was a young boy in the 1940s, visiting Centre Island was high adventure. It was during the war years, and holidaying within the city was the only possibility open to most people. Gasoline and car tires were rationed, and automobiles were unaffordable. Besides, cars were not being manufactured due to the war effort. The most popular summer destinations were Centre Island, Sunnyside, and in mid-August, the CNE. The CNE is now greatly reduced in size and Sunnyside Amusement Park was demolished to construct the Gardiner Expressway. Sadly, the village on Centre Island, which I knew as a boy, has also disappeared.

For my family, a day-trip to Centre Island always began when my family boarded a Bay Streetcar. In those years, the Bay cars journeyed from their western terminus at St. Clair and Lansdowne, east on St. Clair, south on Avenue Road, east on Davenport and then, southward on Bay Street to the ferry docks at Bay and Queen’s Quay.

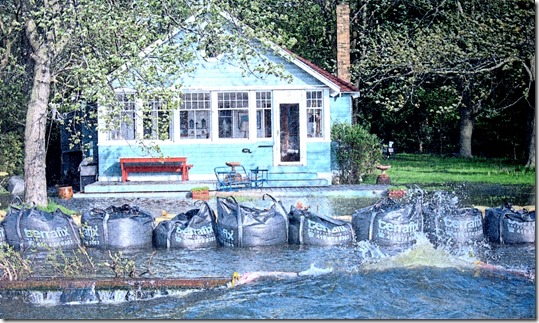

The excitement of anticipation caused the journey on the streetcar to be akin to a trans-continental trip. However, after travelling southward through the Bay Street canyon, we finally arrived at the ferry terminal, on the south side of Queen’s Quay, at the foot of Bay Street. My dad referred to as “the new terminal,” as it had been built between the years 1926 and 1927. This was only a few years after he had arrived in the city as a young immigrant in 1921.

As a boy, this was the only terminal that I knew; it remained in service until 1972, when it was demolished. The present-day facility, the Toronto Island Ferry Docks, was built in 1973, and was renamed the Jack Layton Terminal in 2013. In 2015, it was announced that a more modern terminal is to replace it.

This photograph of the terminal was taken in 1927, shortly after it opened at the foot of Bay Street. This is the terminal I knew as a boy.

In the 1940s, the ferries that carried passengers across the harbour were the Bluebell (launched in 1906), Trillium (1910), the William Inglis (1935) and the Sam McBride (1939). They were all double-decked, double-ended boats. My favourite was the Trillium, as my father always took my brother and me below deck, where it was possible to view the enormous pistons that powered the side-paddles that propelled the boat across the waters of the bay. The sheer size and hissing noise of the pistons were amazing and fascinating. Thankfully, the Trillium still exists today and is available for special harbour excursions.

The only terrifying incident I experienced on a ferry was aboard the Bluebell. My uncle George was the captain in the 1940s, and on one occasion, he invited us to climb up to the wheel-house on the top deck. The only problem was that to reach it, I needed to ascend an iron ladder attached to the side of the boat. While on the ladder, I was virtually hanging in space, the waters of the harbour threateningly swirling below me. Reaching the top, I enjoyed the view from the windows of the wheel-house, but descending the ladder was even more frightening than the witch in the glass booth in the ferry terminal.

The Bluebell in the 1940s, when my Uncle George Brown, was the captain of the ferry. Toronto Public Library, 9646-40.

After crossing the harbour and arriving on Centre Island, we walked along a cement pathway that remains in existence today. On either side of it were expansive picnic grounds and a large pavilion with many tables. Under it, picnickers could find shelter from the sun on scorching hot days or from thunderstorms on rainy afternoons. Eventually, we reached the Venetian-style bridge that crossed over Long Pond, one of the many lagoons on the islands. On the south side of the bridge was Manitou Road, the main drag of the village on Centre Island. It was a relatively short in length, about equal in distance to King Street, between Spadina Avenue and Bathurst Street. However, its size did not detract from its importance.

The Venetian-style bridge over Long Pond in 1900. View gazes south. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1568, Item 0433.

After crossing the bridge, at the north end of Manitou Road, beside the lagoon, there was a boathouse that rented canoes by the hour or day. Paddling the quiet waters of the islands had been popular since the 19th century. However, my eyes were not drawn to the canoe-rental shop, but to the food stands on Manitou Road. I longed to feast on the popcorn, candy apples, hot buttered corn (in August), candy floss, and hot dogs. A boy my age was in reality a bag of skin stretched over an appetite.

The food kiosks were not the only places to satisfy one’s hunger. Lining the street were restaurants, where the sounds of the music from the juke boxes drifted on the summer air, their appeal more enjoyable due to the cooling breezes from the lake. “A nickel in the slot” gave a person access to the swinging dance tunes of the decade, such as those of Glenn Miller’s band, which was highly popular during the war years. The candy shop, ice cream parlour, and bakery were mouth-watering, but I ignored the bank, book store, dance halls, open-air dance floor, tea rooms, and drug store. Manitou Road was a complete village contained within a single roadway, since it also possessed a Dominion Bank, laundry, dairy, and butcher shop.

Lining the street were hotels and Victorian or Edwardian wood-frame houses that rented rooms. I heard my my dad tell my mother that the rooms were expensive, so it was not uncommon for two to four young people to share a room. He said that teenagers and young adults ignored the inconveniences of crowded rooms to be close to the action on Manitou Road, where they could “whoop-it-up” and misbehave, as they were beyond the prying eyes of their parents and neighbours across the harbour in the city.

My mother’s eye-brows rose slightly when my dad informed her that the partying on Manitou Road continued until the midnight hour. He told her that it was a regular occurrence, especially on Friday and Saturdays, or if there were a hot spell that drove Torontonians to escape the heat and humidity on the mainland. As my dad informed my mother about the behaviour of the summer visitors on Manitou Road, I wondered how he knew about such things. Today, I wonder if my mother was thinking the same thing. I won’t relate my mother’s reaction when my dad confessed that when he was younger, he had been in Price’s Casino on Manitou Road.

The side-streets east and west of the main drag mostly had wooden plank sidewalks, shaded by mature trees, many of them ancient willows. These avenues were flanked by rows of wood-frame houses with small gardens. Most of them displayed perennials, as bringing annuals over from the city was inconvenient and laborious. Plants such as hollyhocks, which seeded themselves, as well as blue delphiniums were also popular.

Since no cars were allowed on the islands, residents walked or travelled by bicycle. Adding to the number of bicycles were the rental shops where day-trippers could lease them by the hour or day. Other activities included tennis, bowling, canoeing, and badminton. At the south end of Manitou Road were the cool waters of Lake Ontario. Beside it was the avenue simply named the Lakeshore, a long stretch of roadway that paralleled the Lake. Following it to the west led to Hanlan’s Point, and to the east, Ward’s Island. Some of the finest homes on the islands were on the Lakeshore, facing the water. Many prominent Toronto families maintained summer homes on Centre Island, including the Gooderham’s and the Massey’s. These two families were also instrumental in creating the Royal Canadian Yacht Club (YCYC) on Centre Island.

On the west side of the intersection of Manitou Road and the Lakeshore was one of the most popular beaches on the islands. The long stretch of golden sand was crowded, even when the water was cold, beginning in the morning hours and remaining until about 5:30 pm. After that hour, the crowds thinned out as young people departed for the restaurants, soda fountains, and tea shops on Manitou Road. When darkness descended, they would cruise the dance halls, the strings of coloured lights over Manitou Road adding to the party atmosphere. At the end of the evening, unless people were residents, they joined the stampede to catch the last ferry departing for the mainland.

During the 1940s, on most summer days the ferries were crowded to capacity. On August 11, 1944, during a heat wave, they transported 30,000 people across the harbour. In this decade, unless July and August were exceptionally cool or rainy, the ferries carried about a million passengers annually. Most of them were day-trippers. During the summer months, the number of residents living on the islands swelled to about 12,000, though some remained after the warm weather ended. Centre Island was a place that provided entertainment for all ages, with quiet spots for family picnics, lazy lagoons for canoeing, and dance halls and restaurants for younger adults.

However, in 1956, the writing was on the wall. The Centre Island that I knew as a boy was to disappear. The city transferred the responsibility for the islands to the Municipality of Metro Toronto. The official plan was to demolish the permanent buildings and turn the islands into parkland to be shared by everyone, not the privileged few. However, it was mostly the less affluent residents who lost their homes on the islands. No attempt was made to open the grounds of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club to the public. It retains its exclusivity to this very day.

Removing the homes on the islands commenced one of the longest legal battles in the history of the city, as residents fought to maintain their homes. The city was not completely successful in their quest, but the demolition of the homes and the businesses on Manitou Road commenced in the 1960s. I was in my late-teens at this time and remember the reports in the newspapers about the destruction. It was not long before the main drag was razed and the places to “whoop-it-up” were gone forever.

Today, few traces remain of the Centre Island that once existed. However, if a person strolls along the boardwalk that parallels the lake, from Centre Island to Ward’s Island, among the bushes, wild undergrowth and trees, it is possible to view a few surviving cement and stone foundations of the old houses that faced the Lake. Remains of a garden wall or a few steps leading to a doorway can still be seen if one looks carefully. In a few places, there are clumps of perennials that have survived for over six decades, the remains of the quaint gardens that once grew beside the houses that were the summer homes of Toronto residents of yesteryear. These flowers, purchased on the mainland, are now the only living landmarks of a vibrant village life that has disappeared.

The 1960s was an decade when more than just Centre lsland was destroyed. A large number of homes along the Lakeshore Road on the mainland were seized, bulldozed, and paved over to build the Gardiner Expressway. The Sunnyside Amusement Park also disappeared to allow this project to proceed. Within the downtown core, dozens of heritage building, Georgian-style row houses, fine mansions, 1920s-Art Deco skyscrapers, theatres, and government buildings were razed.

Saving the past has never been easy, but the 1960s actively encouraged it. Those who fought against it were labelled as “crackpots” and the enemies of progress.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

Books by the Blog’s Author

“Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book, published by History Press:

Book also available in most book stores such as Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox and AGO Book Shop. It can also be ordered by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

Another book on theatres, published by Dundurn Press, is entitled, “Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again.” It explores 81 theatres and contains over 125 archival photographs, with interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating histories. Note: an article on this book was published in Toronto Life Magazine, October 2016 issue.

For a link to the article published by Toronto Life Magazine: torontolife.com/…/photos-old-cinemas-doug–taylor–toronto-local-movie-theatres-of-y…

The book is available at local book stores throughout Toronto or for a link to order this book: https://www.dundurn.com/books/Torontos-Local-Movie-Theatres-Yesteryear

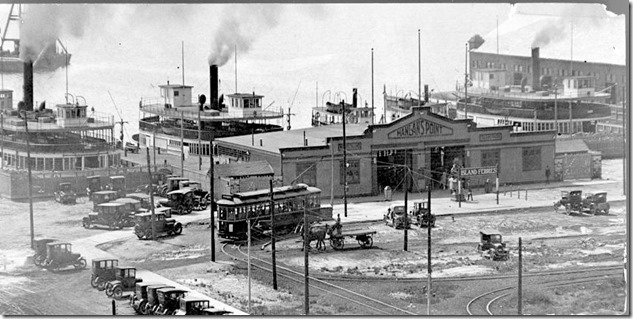

Another publication, “Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. It contains archival and modern photos that allow readers to compare scenes and discover how they have changed over the decades.

Note: a review of this book was published in Spacing Magazine, October 2016. For a link to this review:

spacing.ca/toronto/2016/09/02/reading-list-toronto-then-and-now/

For further information on ordering this book, follow the link to Amazon.com here or contact the publisher directly by the link below:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21

![f1568_it0433[1] 1900_thumb f1568_it0433[1] 1900_thumb](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/f1568_it04331-1900_thumb_thumb.jpg)

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[2] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/cid_e474e4f9-11fc-42c9-aaad-1b66d8522_thumb.jpg)

![image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[2] image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb2_thumb.png)