Government House—”Chorley Park” on July 4, 1924. Toronto Archives, F1548, S 0393, Item 1899.

The term “Government House” is the official title that applies to residences of the Lieutenant Governors in the countries and provinces throughout the British Commonwealth. Ontario’s first Government House was Navy Hall, at Niagara-on-the-Lake, which was occupied by the colony’s first Lieutenant Governor—John Graves Simcoe. After Simcoe relocated the seat of government to York (Toronto) in 1793, a canvas house (tent) technically became Government House, though it is a stretch of the imagination to refer to it as such. In 1800, a governor’s residence was constructed beside Fort York, which was torched when the Americans invaded the town in 1813.

In 1815, the government purchased the home of Chief Justice John Elmsley to provide a residence for the lieutenant governors. It was located at King and Simcoe Streets. A new residence was built in 1870 on the same site as Elmsley House. However, as the land surrounding it became increasingly industrial, another site was sought. The Government House, built in 1870, was sold in 1912. After much disagreement and controversy, it was decided that the new vice-regal residence was to be at Chorley Park, in North Rosedale, facing southeast overlooking the Don Valley. Until it was built, the lieutenant governor resided at Cumberland House, a mansion on St. George Street, north of College Street. This house still exists today.

Cumberland House on St. George Street. Photo taken in 2015.

Chorley Park had been named after a town in Lancashire, in England. Government House, which was built within the park, required four year to complete (1911-1915). It was officially opened on November 15, 1915, and was one of the grandest mansions ever constructed in Toronto. Its cost was budgeted at $215,00, but it required over $1,000,000 to complete. An impressive driveway from Roxborough Drive led to a grand circular terrace, and from there, a concrete bridge led to a forecourt in front of the mansion. The forecourt was intended for formal outdoor receptions and vice-regal events. There was another driveway from Douglas Drive.

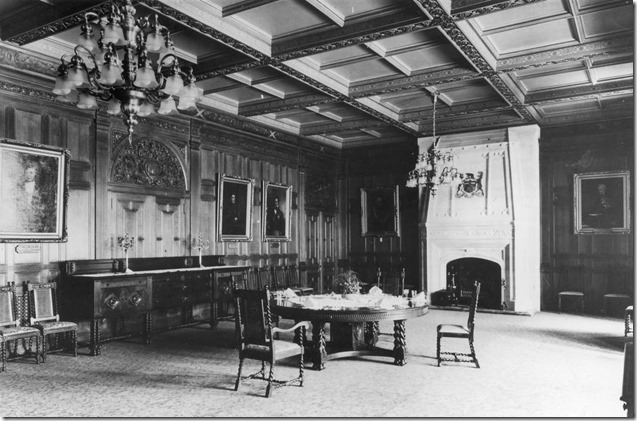

Chorley Park’s architect was Francis R. Hawkes, who also designed the Whitley Building at Queen’s Park and the Mining building at the University of Toronto. For Government House, he chose the French Chateau style. The Canadian Pacific Railway’s chain of hotels employed the same architecture, the Royal York Hotel being a prime example. The Chorley Park mansion resembled a castle-like structure, reminiscent of those in Loire Valley in France. Symmetrical in design, it was richly ornamented, containing many turrets and pinnacles, even the chimneys architecturally decorated. Constructed of grey Credit Valley limestone, its multiple roofs were of red ceramic tiles. The front reception hall was three storeys in height, lit by a skylight, with galleries surrounding it. The hall resembled the one that today is in the legislative building at Queen’s Park. The state dining room was richly panelled in oak. All public rooms had grand vistas of the Don Valley. The formal gardens surrounding the mansion were designed by C. W. Levitt of New York.

However, the cost of maintaining the mansion increased each year. After the Great Depression began in 1929, the dollars spent to maintain Chorley Park became a political embarrassment. In 1934, Mitchell Hepburn was elected premier, one of his campaign promises being to trim government expenses. Chorley Park was an obvious target. Its official function as Government House ceased in 1937, and the furnishings and contents of the mansion were disposed in an auction.

The house was purchased in 1940 by the Federal Government for a military hospital, but this ended 1953. During the Korean War, it was employed as a training and recruitment facility. Later, it housed refugees escaping the Hungarian revolution of 1956. It was bought by the City of Toronto in 1960 for $100,000, and the following year, it was demolished to create a public park. Only the concrete bridge that gave assess to the residence from the grand circle survives as a reminder of the glory days of the vice-regal mansion. Today, there are trails that lead from the park down into the Evergreen Brick Works in the Don Valley.

Ontario is the only province that today has no Government House. Its lieutenant governors have a suite in the west wing of the legislature at Queen’s Park for receptions, and live in private homes of their own choosing.

Sources: torontoist.com torontothenandnow.blogspot.com torontoplaques.com torontohistory.net “Lost Toronto” by William Dendy.

The location of Government House in Chorley Park.

View in 1911 of the entrance to Government House from Roxborough Drive and the circular terrace, when it was under construction. The bridge connecting the circular terrace and the forecourt is visible. Toronto Archives, F1244, Item 3102.

View of Chorley Park after 1900, from the driveway from Roxborough Drive, which led to the circular terrace. Toronto Archives, F1568, Item 10086.

State dining room c. 1915. Toronto Archives, F1244, Item 2411.

Artist’s rendition of Chorley Park c. 1915. The circular terrace is visible, and the small bridge leading to the forecourt in front of the mansion. Ontario Archives, 10031416.

An aerial view of Chorley Park c. 1930. It reveals the two entrances, one of them from Roxborough Drive (on the south) and the other from Douglas Drive. Toronto Archives F1244, Item 10086.

Aerial view of the two driveways, the circular terrace, the forecourt, and the mansion. Toronto Archives, F1244, Item 1128.

View of Chorley Park from the forecourt, in 1925. Ontario Archives, 10012487.

Reception in the forecourt in 1925. Ontario Archives, 10031278.

Government House on August 3, 1928. Toronto Archives, S0071, Item 6102.

Chorley Park in 1961, when it was being demolished. Ontario Archives, 10013933.

Chorley Park during demolition in 1961. Ontario Archives, 10013935.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

The publication entitled, “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Shop, and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

Another book on theatres, published by Dundurn Press, is entitled, “Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again.” It contains over 125 archival photographs and relates interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating histories.

The book is available at local book stores throughout Toronto or for a link to order this book: https://www.dundurn.com/books/Torontos-Local-Movie-Theatres-Yesteryear

Another publication, “Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. For further information follow the link to Amazon.com here or contact the publisher directly by the link below:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21

![July 4, 1924. f1548_s0393_it18999b[1] July 4, 1924. f1548_s0393_it18999b[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/july-4-1924-f1548_s0393_it18999b1_thumb.jpg)

![Chorley_Park_Map[1] Chorley_Park_Map[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/chorley_park_map1_thumb.jpg)

![after 1900- f1568_it0227[1] after 1900- f1568_it0227[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/after-1900-f1568_it02271_thumb.jpg)

![c. 1915, Ont. A. I0031416[1] c. 1915, Ont. A. I0031416[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/c-1915-ont-a-i00314161_thumb.jpg)

![1925- Ont. A. I0012487[1] 1925- Ont. A. I0012487[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/1925-ont-a-i00124871_thumb.jpg)

![reception, 1925, Ont. A. I0031278[1] reception, 1925, Ont. A. I0031278[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/reception-1925-ont-a-i00312781_thumb.jpg)

![demolition, 1959, Ont. A. I0013933[1] demolition, 1959, Ont. A. I0013933[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/demolition-1959-ont-a-i00139331_thumb.jpg)

![demolition, 1959, Ont. A. I0013935[1] demolition, 1959, Ont. A. I0013935[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/demolition-1959-ont-a-i00139351_thumb.jpg)

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/cid_e474e4f9-11fc-42c9-aaad-1b66d8521_thumb.jpg)

![image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[2] image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb2_thumb.png)