The worst snow storm to ever descend upon Toronto was in December of 1944. It holds the record as the most snow that ever fell on the city within a 24-hour period. It was a greater volume of snow than the year Mayor Mel Lastman called in the army to help clear the streets.

City of Toronto Archives, Series 372, Sub Series 100, Item 455

Toronto’s Yonge Street, looking north from Adelaide Street, as a TTC streetcar struggles to provide service to the snow-filled street.

City of Toronto Archives, Series 372, Sub Series 100, Item 452

George Street, looking north to Adelaide Street East. The street had no public transit on it, so it remained unplowed. Other than the main streets, most of the city’s avenues remained in this condition for several weeks.

City of Toronto Archives, Series 100, SS 0372, Item 450

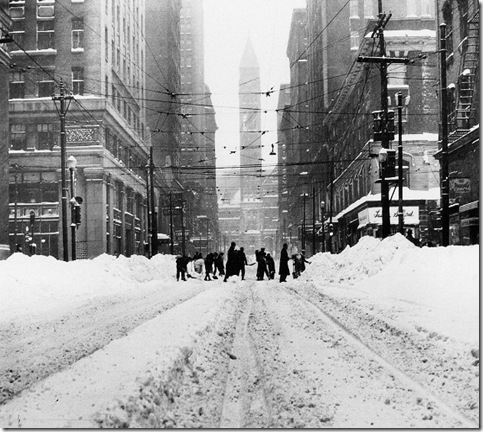

Looking north on Bay Street to the Old City Hall.

The account of the storm that descended on Toronto in December of 1944 is contained in the book “Arse Over Teakettle.” It is a novel about a family coping with the turmoil inflicted by the Second World War.

An event occurred in early December of 1944, the images of which remain with me today. The worst snowstorm in Toronto’s history inundated the city. It was rare that stories linking Canada and snow were considered newsworthy. In other countries, they usually ranked them in the same category as an old bachelor’s love life—frigid, but who cares? However, this was an exception, as the event created newspaper headlines across North America.

A warm, moist air mass travelled for several days northward up the Mississippi Valley from the Gulf of Mexico. Its effects were first felt in Colorado; it continued northward, gradually spinning to the northeast. It reached northern New York State in the early evening of Monday, 11 December, sweeping westward below the Niagara Escarpment and across Lake Ontario. Then, changing direction, it approached Toronto from the east. Before it blew out to sea off the Atlantic seaboard, it created a wide swath of death and destruction.

Even today, lake-effect storms remain the city’s worst winter nightmare. The famous “storm of ’44” began on a Monday evening, when snow flurries scattered across the streets and laneways. Soon, its intensity increased. My dad glanced out the window at the thick mass of swirling flakes and said, “I hope the snow keeps up.”

My mom replied, “Are you crazy?”

“No!” he affirmed. “If it keeps up, then it won’t come down.”

My mom replied, “I never knew that corn could grow during a snowstorm.”

My dad said nothing more. He hoped that his silly remark had hidden his concerns about travelling to work in the morning, as he knew it might be difficult, if not nearly impossible. He didn’t want my mom to worry.

As midnight approached, the storm intensified. In the early hours of the morning of 12 December, Torontonians awoke to a wintry world beyond imagination. By 8:00 a.m., nineteen inches (nearly fifty centimetres) had fallen. The storm continued, and by 10:00 a.m., there were twenty inches, twenty-one by noontime. Before the storm abated in the afternoon, twenty-two and a half inches of snow had accumulated.

Because of the gale-force winds, drifts were six to ten feet high. The previous record snowfall was in 1876, with 16.2 inches (41.1 cm). During the snow crisis of 1999, when Mayor Mel Lastman called in the army, 15.5 inches (39.3 cm) fell. The 1944 storm still holds the record as the greatest amount of snow from a single storm.

When people awoke and gazed out their frost-covered windows, it appeared as if an enormous snow-filled dumpster had dropped its contents, burying the city. Streets and laneways were impassable, sidewalks were blocked with drifts, fences were buried, and most garden sheds had vanished beneath a thick layer of white. Other than the wind, the only sounds were the muffled clip-clops of a few horse carts whose owners foolishly braved the drifts.

One newspaper reporter wrote, “It’s as if a giant’s hand has silenced the city.”

On the radio, Mayor Conboy issues a request to the people of Toronto: “Remain within your homes, and do not travel to work unless necessary. Any available public transportation has been reserved for emergencies and those employed in the war industries, as their production is essential for victory. Cars are banned from roadways with streetcar lines. Get into the national spirit and help our city support the war effort.”

Despite these restrictions, it was hopeless. The city moved in slow motion. Hospitals were short staffed; they postponed surgeries. On the radio, Bell Telephone notified customers that no repair trucks were available and asked them to limit their phone calls. Funerals were cancelled. Milk and bread deliveries were impossible. Courts of justice were shut down when jurors failed to arrive. The Toronto Stock Exchange ceased operations.

At 11:30 a.m., Premier Drew adjourned the legislative session at Queen’s Park. It was announced, “All activity has ceased.”

On this subject, one newscaster commented, “What’s different? There’s rarely any activity even when the government is in session.”

Eaton’s and Simpson’s closed but vowed to open the following day. However, Eaton’s declared that if any customers arrived at their doors during the storm, they would escort them through the departments.

The University of Toronto suspended all classes for the day, as the campus was buried beneath six-foot drifts. Its ornate Gothic buildings resembled a deserted movie set—eerie, empty, and ghostly. Icy winds whistled through the doorways of the old buildings, bombarding the massive stone walls of University College, Convocation Hall, and Hart House. They wrapped around Memorial Tower, piling the snow under the massive archway. Tornado-like winds hammered the near-vacant quadrangle at the heart of the campus, where a few hearty students struggled through the snowbanks only to be confronted by empty lecture halls.

Officials closed public schools, though many parents were unaware of the announcement and sent their children to school, anyway. One principal reported that of the 530 pupils that normally attended the school, only 60 had arrived. Toronto’s one hundred thousand elementary school children and three thousand teachers had a winter holiday. High schools were in the middle of term examinations and had been scheduled to close on Friday for the Christmas break. Because of the storm, they decided to postpone the exams until the following Monday, the students relinquishing a day of their regular ten-day holidays.