Campbell House’s special exhibition to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the relocation of the historic house from its original location on Adelaide Street to the northwest corner of Queen West and University Avenue.

William Campbell was born in 1758 in Scotland. As a young man, he joined a Highland Regiment and fought in the Revolutionary War and was taken prisoner at Yorktown when Cornwallis surrendered in 1781. In 1784, he settled in Nova Scotia, studied law, and became a barrister. In 1799 he was elected to the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and became Attorney General for Cape Breton Island in 1804.

In 1811, William Campbell relocated to the town of York in Upper Canada, where he was appointed a judge of the King’s bench and presided over many high-profile trials. In 1816, he purchased land on Duke Street (Adelaide Street), where he eventually intended to build a house. In 1818, he was one of the judges at the trial of the men accused of murder, treason, robbery and conspiracy, the charges laid as a result of the rivalry between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Montreal Northwest Company. Campbell also was the judge at the trial of the young Tories who tossed William Lyon Mackenzie’s printing press into the harbour.

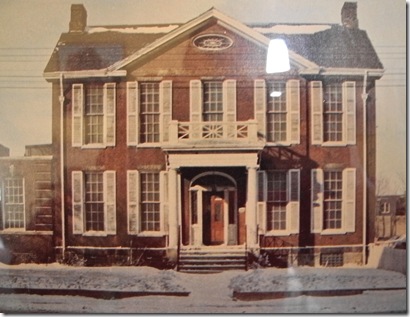

In 1822, he built a house on the land he had purchased on Duke Street. It had an unobstructed view of the lake, since it was on a gentle elevation of land at the head of Frederick Street. It was one of the first brick houses in York, in the heart of the old town. Its postal address was 64 Duke Street (300 Adelaide St). At the time, the population of York was about 2000.

In 1825, he became Chief Justice of Upper Canada (the sixth to hold the position), and the same year was elected speaker of the Legislative Assembly. He retired in 1829 at age 71, and in recognition of his services to the crown he was knighted, becoming the first judge in Upper Canada to be awarded knighthood.

During his retirement years, Sir William was a familiar figure in York. Because of his snow white hair, and the pet alligator that he allegedly took for a walk on a rope, people easily recognized him on sight. A regular attendee at St. James Anglican Church on King Street, he sat in pew on the west side of the centre aisle.

Eventually his health failed. His physician, Dr. Henry, wrote that as Sir Campbell grew weak he was able to tolerate only small pieces of food. The doctor prescribed “snipes”, a tiny bird found at the sandy end of the peninsula, opposite Fort York barracks. Today, the area is part of the Toronto Islands. Several times a week, the doctor rowed over in his skiff to fetch the tiny birds. Campbell existed for over two months on this diet, but the frost came, and the snipes flew away. Sir William was unable to sustain his appetite and died in 1834, at age 76.

The funeral was held in St. James on King Street East, which in those years was a wooden structure with a large gallery. The Legislature was in session at the time, and all the members departed the building to attend the funeral, entering the church as a group, along with barristers and judges. A member of the Lower House had died at the same time, and a “two-fold” funeral was held in the church under the auspices of Archdeacon Strachan. This was an unusual arrangement.

York courier quoted, “At the funeral of the late Sir William, on Monday, there were 20 inhabitants of York, whose ages exceeded 1450 years.” They wore cut-away black coats, up-right collars, frilled shirt-bosoms, white cravats (ornate neck bands), and buckled shoes. Most had milky white hair, either from age or powder.

The funeral was long remembered in the town of York.

Campbell House on its original location on Adelaide Street

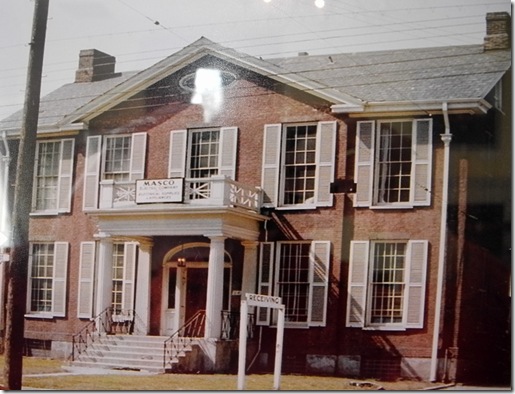

The restored house after it was relocated to Queen West and University Avenue.

Campbell House is “ a mansion in good brick style,” wrote Henry Scadding in 1873. Gazing at the house today, a person can appreciate Scadding’s comment. It was built on stone foundations, Doric pillars supporting its Greek-style portico. The home possesses typical Georgian architectural refinements such as an elliptical fanlight window over the door and sidelight windows, on either side of the the door, to allow plenteous light into the inside hallway. An oval window is in the triangular pediment at the top of the south facade, which has nine large windows with small square panes and shutters are on either side of them. The east and west facades contain two quadrant windows, one on either side of the bricks that contain the chimney flue. These small windows provide light in the attic rooms.

Oval window in pediment in south facade (left) and the quadrant windows on the west facade (right)

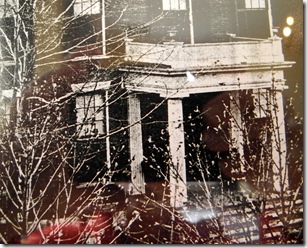

Old porch in previous location (left) and new porch placed on after the restoration (right).

After Sir William Campbell’s death, the home was purchased by the Hon. James Gordon, formerly of Amherstburgh. Then Terence O’Neil lived in it for thirty years. Next was John Strathy and then John Fensom, who resided in it until the late 1890s. By turn of 20th century, the area on Adelaide (Duke) Street was becoming industrial and was no longer viewed as a desirable residential address. Coutts Hallmark (a greeting card company) bought the home in 1962 and added an addition on its west side. In the early 1970s, Coutts Hallmark relocated and offered the building to anyone who would remove it from the property.

The Advocates’ Society, a group of approximately 600 lawyers, formed a foundation to save the house. They pledged $300,000 to the project, and the Ontario Government gave a grant of $50,000. Land on the northwest corner of Queen Street and University Avenue was purchased for the sum of $160,000 from the Canada Life Assurance Company. The total cost of the relocation and restoration was to eventually to cost almost a half million dollars.

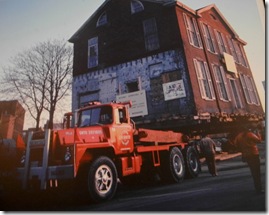

The relocation of the 300-ton house occurred on Good Friday, March 31, 1972. To facilitate the move, a mile of streetcar wire was removed, 82 streetlights swung out of the way, and 65 manhole covers shored up. The house was jacked up 1/16 of an inch at a time, to a height of 10 feet. Fourteen steel support-beams were positioned under it to support its massive weight, which was distributed over 56 rubber tires. It was relocated a distance of one mile, and it required 6 hours.

House being relocated as it slowly passes along the streets of Toronto

It took two years to restore the structure. The inside had suffered much damage, with no traces remaining of the former glorious home of the Chief Justice. In the restoration, the porch was changed, placing four Ionic pillars to support the new half-circle portico. The home was officially opened to the public by the Queen Mother during her visit to Canada in 1974.

The Queen Mother at the official opening of Campbell House in 1972

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

To view previous blogs about movie houses of Toronto—historic and modern

Recent publication entitled “Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” by the author of this blog. The publication explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories of the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses.

To place an order for this book:

Book also available in Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox Book Store and by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791

Another book, published by Dundurn Press, containing 80 of Toronto’s old movie theatres will be released in the spring of 2016. It is entitled, “Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again.” It contains over 130 archival photographs.

A second publication, “Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. This book will also be released in the spring of 2016.

![cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1] cid_E474E4F9-11FC-42C9-AAAD-1B66D852[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/cid_e474e4f9-11fc-42c9-aaad-1b66d8521_thumb1.jpg)