This is my first post about the second book in the “Toronto Trilogy” – “The Reluctant Virgin.”

It is a murder mystery. A cold-blooded serial killer is murdering victims in Toronto in the 1950s. The characters who were of elementary school age in the first book in the trilogy, “Arse Over Teakettle,” are now teenagers. On the Labour Day weekend of 1952, the killer stalks a young woman walking on a dark secluded path in the Humber Valley. The brutality of the murder shocks even the police. There is almost no blood at the death scene, which baffles the two detectives who must solve the crime.

The killer commits further murders in the months and years ahead, selecting various places within the city for the crimes – the Rosedale Ravine, a parking lot behind a pub on the Danforth, a sleazy downtown hotel, a pathway beside Grenadier Pond in High Park, and an outer beach on Centre Island. Because the murder methods and locals appear unrelated, the police are unaware that they are dealing with a serial killer.

In the section below, one of the detectives, Jim Peersen, who is attempting to solve the murders, takes a week’s holiday away from the case to restore his energies. He is dating an attractive young woman, Samantha, who earns her living in the sex trade. To say that his life is complicated is an under-statement. He decides to drive to Stratford to attend the Shakespearean Festival.

This section from the book provides a pleasant diversion from the tension created by the on-going murders. For Toronto residents, it gives insight into the history of a theatrical institution that is well known and loved.

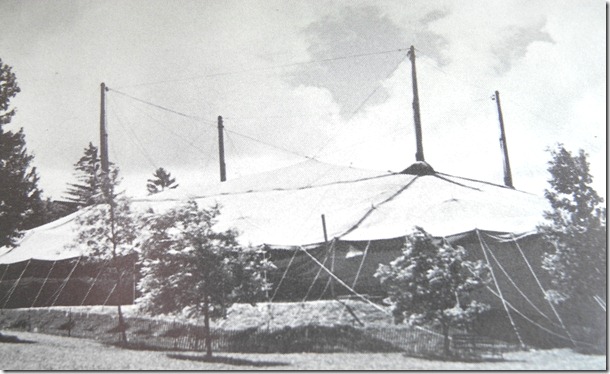

On Saturday 9 July, they set off early in the morning to attend the Stratford Festival of Canada. The Shakespearean festival had commenced two years earlier, held in an enormous tent beside the Avon River in Stratford, a two-hour drive west of Toronto. In its opening season, in 1953, the big attraction had been Alec Guiness in Richard III. The following year, James Mason had captivated the audiences in Oedipus Rex. In this year of 1955, the festival was featuring Julius Caesar, Merchant of Venice, and for the second year, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex.

Following their arrival in Stratford, Jim and Samantha enjoyed lunch, and strolled arm in arm toward the theatre tent, which the festival had purchased in Chicago. Jim had acquired tickets for an afternoon performance of Julius Caesar. Robert Christie was playing Caesar, Lorne Greene, a well-known radio announcer and actor, they had cast in the role of Marcus Brutus, Douglas Campbell was Casca, and William Shatner was Lucius.

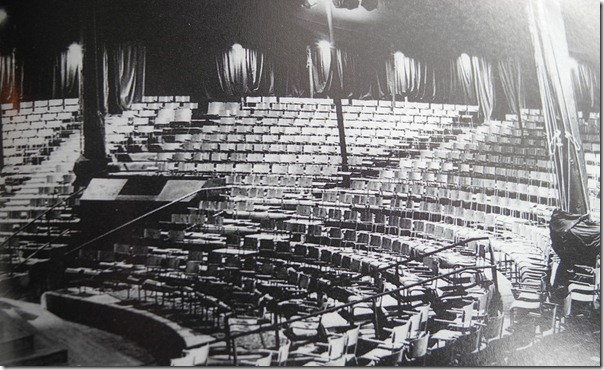

They had erected the tent on the site of today’s Festival Theatre, on the hill overlooking the Avon River. Near the tent was the Stratford Teachers’ College, the building today owned by the festival. When Samantha entered the tent, she was amazed at its enormous size. Its roof soared high above the seemingly endless rows of seats. The stage was surrounded on three sides by the tiered seats, thrust forward into the space normally occupied by the audience. It was the first thrust stage in North America.

Trumpets sounded as Jim and Samantha took their seats. The lights dimmed and darkness fell across the hushed throngs. Then, as the stage-lights slowly rose in a visual crescendo, the actors magically appeared. Flavius Marcullus and several actors dressed as tradesmen faced an audience hushed with anticipation.

Samantha was fascinated from the moment the voice of Flavius echoed across the vast tent. The words painted an image, as if they were alive on the surface of an artist’s canvas—each syllable like a brush stoke, clear and distinct.

“Hence! Home you idle creatures, get you home! Is this a holiday? What, you

know not, being mechanical, you ought not walk upon a labouring day without

the sign of your profession? Speak, what trade art thou?”

The words had hidden meaning for Samantha. “What trade art thou?” The reply on stage had been “carpenter,” but she felt as if Flavius had delivered the line to her, and knew that her reply would be something quite different. She gazed at Jim, but he was absorbed in the production, and had not sensed her personal interpretation of the words. The voice of the blonde at the dance remained in her brain—What trade are you? Slut?…Prostitute?

During the intermission, among the crowds outside the tent, they saw Sam Millford, YCI’s teacher of boys’ P.T., standing on the far side of the lawn. He was accompanied by a young man, perhaps eighteen or twenty years of age, with a handsome face and an athletic build. Before Jim and Samantha were able to approach him, a trumpet fanfare sounded to summon people inside the tent to resume the performance. After another fifty minutes of glorious drama, the play ended with the ringing words of Octavius:

“So call the field to rest, and let’s away, to part the glories of this happy day.”

These words also contained a double meaning for Samantha. After the performance, Jim gazed around at the departing crowds, but did not see Sam Millford and his companion. On the drive home, Jim was relaxed. Samantha wondered if perhaps he was relieved to have witnessed a murder that he was not required to solve. Despite her momentary brooding thoughts, it had indeed been a happy day for her as well.

She thought, All’s well that ends well. A truly Shakespearean sentiment.

The tent at Stratford, first erected in 1953. Photo is from the Stratford archives.

Interior of the tent at Stratford, with the thrust stage surrounded by the seats for the audience. Photo from the Stratford archives.

The Stratford Festival Theatre today.