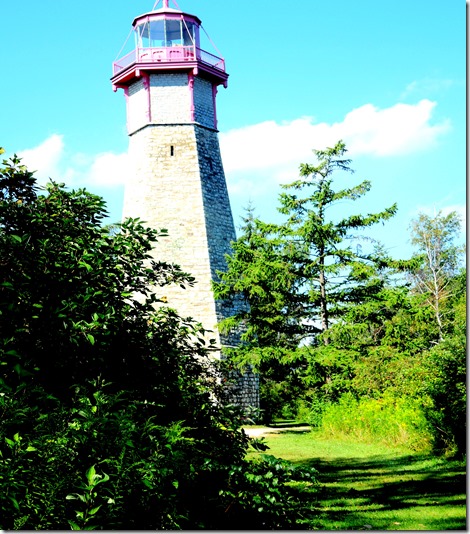

Gibraltar Point lighthouse at Hanlan’s Point, Toronto Islands

Recently I dined at a restaurant located atop one of the city’s towering skyscrapers that overlooks Toronto Harbour. The ever-changing panorama was mesmerizing. The dazzling pinpoints of light from the downtown buildings illuminated the darkness, their brilliance augmented by the many streams of red and white from the myriad of cars snaking along the Gardiner Expressway, Front Street, and the Lakeshore Road.

I tried to imagine the same harbour scene during the last decade of the 18th century, when it would have been enveloped in almost total darkness. The few flickering candles in the windows of the small cabins clustered around the eastern side of the harbour would not have been visible from my modern-day perch. Thankfully, we have a first-hand account of how the islands and the harbour area appeared in those long-ago decades.

In May 1793, Mrs. Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of Lieutenant Governor Simcoe, arrived in Toronto. After the tents, which were to be her home for the forthcoming months, were set-up beside the lake, she commenced exploring, recording and sketching the environs of the settlement. Elizabeth wrote: “We rode on the peninsula opposite Toronto, so I called the spit of land, for it is united to the mainland by a very narrow neck of ground.”

The peninsula is today known as the Toronto Islands, as in later years it was separated from the mainland by a fierce storm that washed away the sandbar at the eastern end of the harbour. How did the peninsula appear in the 1790s?

Elizabeth described it as having “. . . natural meadows and ponds, its poplar trees covered with wild vines, the ground where everlasting peas of purple colour were creeping in abundance, and where wild lilies-of-the-valley grew.” She discovered the sands bordering the open lake, and referred to these as, “my favourite sands.” She visited them time and time again “. . . praising the sweep of the wild fresh air, riding on the hard white surface, watching the antics of unnumbered wild fowl, and listening to the cry of the loons.” The peninsula [today’s Toronto Islands] was reached by boat, a mile across the bay when parties would land on Hanlan’s Point [its modern name]. Elizabeth added, “The Governor thinks the manner in which the sand banks are formed that they are capable of being fortified, he therefore calls it ‘Gibraltar Point’.”

Governor Simcoe thought that the land at the mouth of the harbour was as strategically important to Toronto as the rock that stands guard at Gibraltar, at the entrance to the Mediterranean. Thus, a carriage route was cut along the peninsula to connect the mainland to Gibraltar Point. It later evolved into Lake Shore Avenue, the main east-west axis along today’s Centre Island.

The small colonial town continue to develop. “The bay front and harbour, where it all began, and which for any years the main depot of transportation, was growing in wharves and landing stages. The first to be built was the landing of military stores at the garrison, [and soon] were added added Peter, John and Church Streets.” (Katherine Hale, “Toronto, Romance of a Great City,” Cassell and Company Limited, 1956),

It quickly became evident that it was important to assist ships to enter the harbour safely, to unload their goods at the newly-built wharves. “In 1799, Peter Hunter arrived as the new Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada. . . he instructed that a lighthouse be constructed on Gibraltar Point, built of limestone quarried in Queenston.” (Frederick H. Armstrong, “Toronto, The Place of Meeting,” Ontario Historical Society Windsor Publication, published 1983.)

In 1803 an act was passed by the Provincial Legislature for the establishment of lighthouses. One of them was on Gibraltar Point. According to the act “. . . a fund for the erection and maintenance of such lighthouses was to be formed by levying three-pence per ton on every vessel, boat, raft, or other craft of the burthen of ten tons and upward shall be liable to pay any lighthouse duty . . .”

“. . . a lighthouse was begun at the point of York . . . the Mohawk was employed in bringing over stone for the purpose from Queenston; and that Mr. John Thompson, still living in 1873, was engaged in the actual erection of the building . . . (“Toronto of Old,” Henry Scadding).

In the decade when the lighthouse was being built, “The peninsula in front of York was plentifully stocked with goats, the offspring of a small colony established by order of Peter Hunter at Gibraltar Point for the sake, for one thing, of the supposed salutary nature of the whey of goat’s milk. These animals were dispersed during the War of 1812-1815.” (“Toronto of Old,” Henry Scadding).

The lighthouse was completed in 1808, the walls six-feet thick at its base. It was “a hexagon tapered tower, 52 feet high, on a six-sided oaken crib, with a wooden lantern cage 18 feet high above the stonework. In 1832, a perpendicular addition of stone atop the tapered tower increased the height of the lighthouse by 12 feet, making it 82 feet to the vane. The lantern cage was later replaced by an iron one, when a change was made from a fixed light, burning 200 gallons of whale oil a year, to a revolving occulting light of greater power, operated by a clockwork mechanism.” (Source: “Historic Toronto, Toronto Civic Historical Committee, February 1953.”).

The first lighthouse keeper, J. P. Rademuller, a German who had immigrated to Upper Canada. He kept watch at Gibraltar Point for enemy ships and friendly vessels returning to a safe harbour at York. He was in residence at the lighthouse during the Battle of York in 1813, when American ships invaded the town of York.

The lighthouse was in a secluded location, and its glowing beacon was easy to spot. As a result, it became a focal point for smugglers that wished to avoid taxes on imported goods, particularly alcohol. Some sources state that it was common knowledge that Rademuller kept a supply of home-brewed ale in his home beside the lighthouse. John Paul Rademuller disappeared under mysterious circumstances on January 2, 1815. It was alleged that he had been murdered by two soldiers who had been enjoying his home-brewed beer. They were arrested but eventually set free as there was insufficient evidence—Rademuller’s body was never found.

One version of the story states that Rademuller was killed after the soldiers bought the beer, but complained that its alcoholic content was low as it had become frozen during the cold winter weather. They felt that the lighthouse keeper was trying to rip them off. Whether or not this was true, most sources agree that Rademuller was killed that night and dismembered by his killers, who buried his body parts in various graves near the lighthouse. His ghost is said to still haunt the site.

The story of the murder was recorded by John Ross Robertson in his book, “Landmarks of Toronto”, written in 1908, and it has become a source for ghost stories ever since. But Robertson raises scepticism that the event ever occurred. He admitted that he had learned the details from the current lighthouse keeper in the 1870s, George Durnan, who had apparently gone looking for a body and had dug up a coffin containing a jawbone. Despite this, the historic plaque on the lighthouse mentions the ghost story and the jawbone, although many historians thought that this was not appropriate as it was not a proven fact. (For a link to discover more information about the murder, https://torontoist.com/2017/08/spooky-story-behind-gibraltar-point-lighthouse, and spacing.ca/toronto/2015/04/30/true-story-torontos-island-ghost/ )

The painting on the left entitled, “View of York,” c. 1815,” is by Robert Irvine, and is today in the collection of the AGO. The painting depicts the lighthouse on Gibraltar Point in 1815. Irving was captured in September of 1813, during the War of 1812, and released from an American prison in September 1814. After the war, he was employed by the military and lived in York until 1817. In April 1830, records reveal that he was residing in Scotland. (Source: “Government of Fire,” Frank A. Dieterman and Ronald F. Williamson, Archaeological Services, 2001).

When completed, the lighthouse was the tallest structure in the city and remained so for nearly 50 years. Its power source was switched to coal-oil in 1863 and, then, to electric in 1916. The lighthouse still stands, but it no longer guides ships as it did for over a hundred years. It is still on Gibraltar Point, although because of the silt that has built-up over the years, the tower is now about 100 meters from the water’s edge. It was decommissioned in 1958, and is Toronto’s oldest building situated on its original foundation.

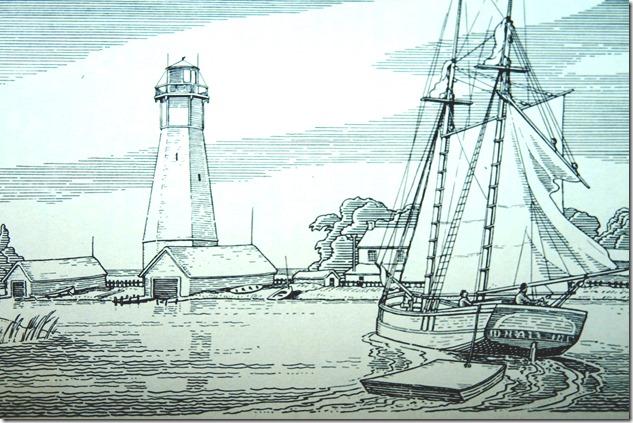

Sketch of the lighthouse and the lighthouse keeper’s cottage in 1894. Toronto Public Library, r-450.

Undated sketch of the lighthouse from the book “Historic Toronto,” by the Toronto Historical Society, published in 1953. Today, the structure is no longer at the edge of the water. Because of the silt that has been deposited on the shoreline, it is 100 metres from the water.

Watercolour depicting ships off Gibraltar Point in 1894. Toronto Public Library 987-10-2

Gibraltar Point Lighthouse in 1915. Ontario Archives F-4336.

View gazing west at the lighthouse on Gibraltar Point in 1919, with private summer cottages lining the shoreline. Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231, item 10156.

Lighthouse in 1940, Toronto Public Library, 10013724.

View from the base, where the stones are six-feet thick. Photo taken in 2010.

Door that opens to the steps to ascend to the top of the lighthouse. The door faces east.

Historic plaque on the lighthouse

Top of the structure where the lamp was located. The stones for the top of the towering lighthouse were quarried in Kingston.

Limestone base of the tower, the stones brought across the lake from Queenston.

To view the Home Page for this blog: https://tayloronhistory.com/

For more information about the topics explored on this blog:

https://tayloronhistory.com/2016/03/02/tayloronhistory-comcheck-it-out/

Books by the Blog’s Author

“ Lost Toronto”—employing detailed archival photographs, this recaptures the city’s lost theatres, sporting venues, bars, restaurants and shops. This richly illustrated book brings some of Toronto’s most remarkable buildings and much-loved venues back to life. From the loss of John Strachan’s Bishop’s Palace in 1890 to the scrapping of the S. S. Cayuga in 1960 and the closure of the HMV Superstore in 2017, these pages cover more than 150 years of the city’s built heritage to reveal a Toronto that once was.

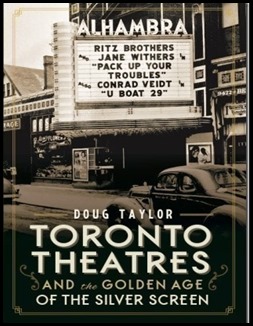

“Toronto’s Theatres and the Golden Age of the Silver Screen,” explores 50 of Toronto’s old theatres and contains over 80 archival photographs of the facades, marquees and interiors of the theatres. It relates anecdotes and stories by the author and others who experienced these grand old movie houses. To place an order for this book, published by History Press:

Book also available in most book stores such as Chapter/Indigo, the Bell Lightbox and AGO Book Shop. It can also be ordered by phoning University of Toronto Press, Distribution: 416-667-7791 (ISBN 978.1.62619.450.2)

“Toronto’s Movie Theatres of Yesteryear—Brought Back to Thrill You Again” explores 81 theatres. It contains over 125 archival photographs, with interesting anecdotes about these grand old theatres and their fascinating histories. Note: an article on this book was published in Toronto Life Magazine, October 2016 issue.

For a link to the article published by |Toronto Life Magazine: torontolife.com/…/photos-old-cinemas-doug–taylor–toronto-local-movie-theatres-of-y…

The book is available at local book stores throughout Toronto or for a link to order this book: https://www.dundurn.com/books/Torontos-Local-Movie-Theatres-Yesteryear

“Toronto Then and Now,” published by Pavilion Press (London, England) explores 75 of the city’s heritage sites. It contains archival and modern photos that allow readers to compare scenes and discover how they have changed over the decades. Note: a review of this book was published in Spacing Magazine, October 2016. For a link to this review:

spacing.ca/toronto/2016/09/02/reading-list-toronto-then-and-now/

For further information on ordering this book, follow the link to Amazon.com here or contact the publisher directly by the link below:

http://www.ipgbook.com/toronto–then-and-now—products-9781910904077.php?page_id=21

![1894 sketch pictures-r-450[1] 1894 sketch pictures-r-450[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1894-sketch-pictures-r-4501_thumb.jpg)

![off Gibral. Point 1884 Tor. Pub. 987-10-2[1] off Gibral. Point 1884 Tor. Pub. 987-10-2[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/off-gibral-point-1884-tor-pub-987-10-21_thumb.jpg)

![f1231_it1015b[1] 1909 f1231_it1015b[1] 1909](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/f1231_it1015b1-1909_thumb.jpg)

![1940, Toro Pub. I0013724[2] 1940, Toro Pub. I0013724[2]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1940-toro-pub-i00137242_thumb.jpg)

![image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1] image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb[1]](https://tayloronhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/image_thumb6_thumb_thumb_thumb_thumb1_thumb2.png)