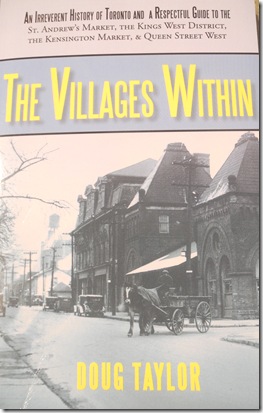

The passage below is from the book “The Villages Within,” nominated for the 2011 Toronto Heritage Awards. This section of the book tells about the historic St. Andrew’s Market, the second market established by Toronto during the nineteenth century. The St. Lawrence Market was the city’s first.

During the late 1830s, it was becoming obvious that the St. Lawrence Market was too distant to serve the needs of the residents of Toronto who were increasingly building homes to the west of Peter Street. As a result, the city planned a new market square, the land grant dated May 22, 1837. The northern end of the square was to be 337 feet long, fronting on Richmond Street, and the depth was to be 173 feet. The site consisted of one and three-quarters acres. On the east, the market boundary was Brant Street, with Maud Street on the west, and Adelaide Street on the south. In 1837, because few residents were dwelling in the area, the creation of the new market square was not a heralded event.

It is not certain when the citizens of early-day York commenced attending the market in the square created in 1837. However, it is likely that sometime during the 1840s, a small seasonal market was held on Saturday mornings, attended mostly by women, as the majority of the men were required to work at their places of daily employment, Saturday being a workday.

Slowly the market grew in size, and in 1850, the city hired the architect Thomas Young to design a frame building to protect shoppers from the weather. Young, born in England in 1805, had previously designed King’s College, Toronto, and the wooden building for the St. Patrick’s Market on Queen Street.

Maps of the period reveal that the wooden St. Andrew’s Market building was constructed in the centre of the market square and contained generous interior space for stalls. A police station and a fire bell were also located within the building. Along the outside walls were produce stands, with canvas awnings sheltering the patrons from the hot summer sun and the rains of spring and autumn, as well as the snows of winter. At the south end of the square, on Adelaide Street, they erected a shelter to protect the horses from the elements. The remainder of the square was green space to accommodate carts, wagons, and the Saturday-morning shoppers. Friends greeted friends, in the background the sound of neighing horses and rumbling wagon wheels.

In 1857, only the St. Lawrence, at King and Jarvis streets, exceeded the importance of the St. Andrew’s Market. On a busy Saturday morning, the carriages and horses, as well as the numerous carts of the citizens of Toronto, crowded St. Andrew’s Market. It was a gathering place to socialize and chat with friends and neighbours. Housewives purchased vegetables, grains, meat, and fish.

A resident of Toronto wrote, “At Christmas time, the abundance of the market would do credit to any city in the world.”

Though this was exaggeration, it expressed the writer’s pride as he gazed at the abundance of the Christmas market, where many rows of dressed fowl hung from numerous poles suspended above the stalls and shops, whole pigs and sides of beef adding to the display. Counters with an array of beef, pork, and lamb greeted the eyes, alongside baskets of fresh eggs. Bushels of root vegetables were positioned side by side and in some shops were stacked against the rear walls. At Christmas, even the fish stalls managed to display fresh product.

It was an amazing Yuletide scene.

In 1873, a handsome grand hall was finally erected. It was an attractive building of white brick, designed in the Renaissance style and appropriately named “St. Andrew’s Hall.” The former building had been located in the centre of the square, but the new structure was erected at the north end of the property, fronting Richmond Street.

In 1889, a red-brick Annex was built to the west of the St. Andrew’s Hall, to house shops and stalls selling vegetables, meat, hay, and feed supplies. This was an attempt to lure farmers away from the St. Lawrence Market.

In an open area between the Hall and Camden Street was a “weigh house” to verify the weight of the various products that entered the market. Today, the apartments facing west at 50 Camden overlook the spot.

If a person were to visit the St. Lawrence Market of today during the Christmas season, and view the area where the butchers’ stalls are located, he/she would have an idea of how the St. Andrew’s Market appeared in the 1870s. Butchers dominated the scene, with a vast array of meats, especially poultry. On Saturday mornings, in the 19th century, farmers from outside the city brought their produce to the market by horse and wagon and occupied the stalls around the outside of the market building, as well as any available space inside, particularly when the weather was inclement. Their tables and stalls would appear similar to the North Building of today at the St. Lawrence Market, where farmers sell jams, preserves, and breads, as well as their fruits and vegetables. St. Andrew’s Market also had a general store, supplying packaged and dry goods. It was a noisy, bustling scene, as merchants called out to attract customers to their shops and stalls.